"Why did Hashem (G-d) say there should be no sex during niddah? So the woman should be loved on her husband like a bride entering her wedding."

Editor's note: Many non-Jewish feminists have condemned the religious practices discussed in this article as sexist and anti-woman. As a non-Jewish woman, it is easy for me to see how one who does not understand the culture of Judaism could come to that conclusion. However, after discussing the subject at length with the author and others familiar with the practice, and then reading this article, I’ve come to understand that those interpretations of the laws of Niddah are based on opinion rather than fact. I hope the reader walks away with a new respect for these practices.

Many cultures throughout history, and even some still today, have rituals which evolve around a woman’s menstrual cycle. Every culture has individual ideas or theologies concerning this natural process. Today, the most common way the Western World is exposed to the Jewish Religious view of a woman’s menstrual cycle is in the words of the Bible.

In the book of Leviticus – a book of the Jewish Torah and also the Christian Bible – is found a sequence of verses which give laws concerning a women when she is menstruating. Here the concept of “clean” and “unclean” concerning this natural process is introduced. These verses became the basis for the laws of Niddah and are expounded on in the Talmud.

When looking at the verses in Leviticus, it is important to remember these laws were given to the Jewish Nation as part of other laws in relation to service in the Holy Temple. From all the numerous laws given in connection to service in the Holy Temple, this law alone is still practiced today. To the Jewish couple, continuing this practice is a way to bring holiness and much more into the family.

“One of the most widely misunderstood concepts in the Torah is contained in the words tum’ah and taharah. Translated as ‘unclean’ and ‘clean,’ or ‘impure’ and ‘pure,’ tum’ah and taharah—and, by extension, the laws of Niddah and Family Purity—often evoke a negative response. Why, it is asked, must a woman be stigmatized as tamei, ‘impure’? Why should she be made to feel inferior about the natural processes of her body?” asks Susan Handelman in On the Essence of Ritual Impurity.

In reality, those who live by the laws of Family Purity don’t find them to be harsh or sexist. Instead, they are happily embraced by many in Jewish religious communities. When you ask an Orthodox Jewish wife what is the key to keeping her marriage fresh and new after years of marriage, they will often say Family Purity.

Judaism practices living a life that not only promotes family harmony, but injects into the midst of the family a sense of purity and holiness. One part of this concept is adhering to the laws of Niddah and Family Purity.

Many people who are not Jewish see these laws as sexists or degrading. From the outside looking in, it is easy to see why. In the Western World the term “unclean” is often perceived as something that is nasty or unfit. However in the Jewish Culture, this is not the case. First and foremost, it is important to remember that being “unclean” is not a physical concept but rather spiritual.

“The laws of tum’ah, niddah and mikvah belong to the category of commandments in the Torah known as chukkim—Divine “decrees” for which no reason is given. They are not logically comprehensible, like the laws against robbery or murder, or those commandments that serve as memorials to events in our national past such as Passover and Sukkot.” The basis for these laws today date back to the giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai and have been practiced for 3,325 years.

These concepts can be deep and confusing at times. Without consulting a Rabbi and taking the time to fully study them, they are easily misinterpreted. For the purpose of this article, I would like focus on how these laws affect my marriage, rather than their theological meanings or the ritual acts.

Many cultures throughout history, and even some still today, have rituals which evolve around a woman’s menstrual cycle. Every culture has individual ideas or theologies concerning this natural process. Today, the most common way the Western World is exposed to the Jewish Religious view of a woman’s menstrual cycle is in the words of the Bible.

In the book of Leviticus – a book of the Jewish Torah and also the Christian Bible – is found a sequence of verses which give laws concerning a women when she is menstruating. Here the concept of “clean” and “unclean” concerning this natural process is introduced. These verses became the basis for the laws of Niddah and are expounded on in the Talmud.

When looking at the verses in Leviticus, it is important to remember these laws were given to the Jewish Nation as part of other laws in relation to service in the Holy Temple. From all the numerous laws given in connection to service in the Holy Temple, this law alone is still practiced today. To the Jewish couple, continuing this practice is a way to bring holiness and much more into the family.

“One of the most widely misunderstood concepts in the Torah is contained in the words tum’ah and taharah. Translated as ‘unclean’ and ‘clean,’ or ‘impure’ and ‘pure,’ tum’ah and taharah—and, by extension, the laws of Niddah and Family Purity—often evoke a negative response. Why, it is asked, must a woman be stigmatized as tamei, ‘impure’? Why should she be made to feel inferior about the natural processes of her body?” asks Susan Handelman in On the Essence of Ritual Impurity.

In reality, those who live by the laws of Family Purity don’t find them to be harsh or sexist. Instead, they are happily embraced by many in Jewish religious communities. When you ask an Orthodox Jewish wife what is the key to keeping her marriage fresh and new after years of marriage, they will often say Family Purity.

Judaism practices living a life that not only promotes family harmony, but injects into the midst of the family a sense of purity and holiness. One part of this concept is adhering to the laws of Niddah and Family Purity.

Many people who are not Jewish see these laws as sexists or degrading. From the outside looking in, it is easy to see why. In the Western World the term “unclean” is often perceived as something that is nasty or unfit. However in the Jewish Culture, this is not the case. First and foremost, it is important to remember that being “unclean” is not a physical concept but rather spiritual.

“The laws of tum’ah, niddah and mikvah belong to the category of commandments in the Torah known as chukkim—Divine “decrees” for which no reason is given. They are not logically comprehensible, like the laws against robbery or murder, or those commandments that serve as memorials to events in our national past such as Passover and Sukkot.” The basis for these laws today date back to the giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai and have been practiced for 3,325 years.

These concepts can be deep and confusing at times. Without consulting a Rabbi and taking the time to fully study them, they are easily misinterpreted. For the purpose of this article, I would like focus on how these laws affect my marriage, rather than their theological meanings or the ritual acts.

Great article, Thanks so much for the information and thanks for the editors note!

This was an awesome read, I am very intrigued by Judaism and the cultural/religious aspects of it. Thank you for sharing this!

What an amazing article. Given me so much to think about in terms of my approach to my marriage and given me a sneak peek in to a religion that has always fascinated me. Thank you for sharing.

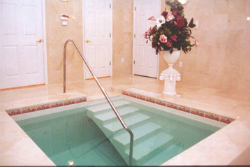

I am so amazed that you enjoyed this article. All of the positive reaction has convinced me to work on more articles about the Mikvah

Do you have any references regarding male fertility increasing after abstaining for 2 weeks? We're dealing with MFI and have been told that after three days, the quality of the sperm goes down as they die.

@ gothicwhispers.... the information originally came from my Rabbi, the Mayo clinic agrees and some other fertility web sites. this is not to go against your doc. idk there may be something he is referring too. idk.