"If genital mutilation were a problem affecting men, the matter would long be settled."

What is it?

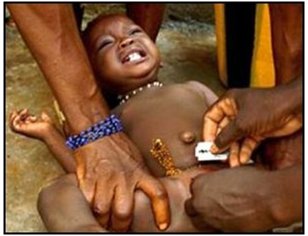

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), sometimes called female circumcision or female genital cutting, is a procedure that intentionally alters the natural female genitalia for non-medical reasons. FGM has no medical benefits and is often performed in third world countries without adequate surgical tools, sterilization, or anesthesia. The majority of FGMs are carried out on children, some still in infancy.

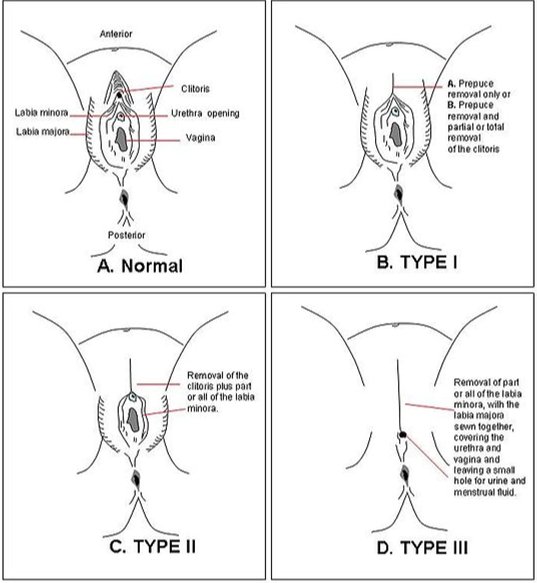

These mutilations occur across the world, even in countries with laws protecting against the practice. The severity varies from ritualistic pricking of the genitals with a sharp object to complete removal of the outer female genitalia. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies FGM into four types:

• Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or prepuce (the folds of skin that house the clitoris)

• Excision: partial or total removal of the clitoris and labia minor, with or without excision of the labia major

• Infibulation: removal of all external genitalia and the stitching together of the two sides of the vulva, typically leaving only a small hole for urination and menstruation

• Other: all other harmful procedures done to female genitalia for non-medical reasons, including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterizing the genitals

Even in minor cases, FGM is a serious and degrading procedure that causes numerous short and long term medical effects, dire sexual and psychological consequences, and is the continuation of centuries of female oppression and sexual violence against women.

Demographics

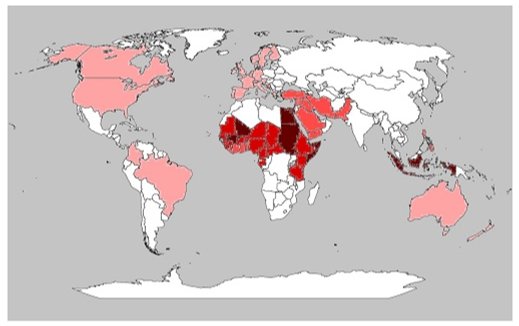

Many people believe that FGM is a small or localized problem, existing solely in Africa. This is false. FGM is neither small in scale, nor localized. In fact, WHO estimates that 140 million girls and women worldwide have already been subjected to mutilation, with six to eight thousand more mutilated every day. This practice is not limited to Africa, but extends to various countries in the Middle East and Asia. It is also known to occur in countries that have laws against the practice including the U.K., U.S., Australia, Canada, and several other industrialized nations (Amnesty Intl.)

The practice is heaviest in 28 countries across central Africa, the southern Sahara, and in parts of the Middle East, with nearly half of the victims of FGM living in Egypt or Ethiopia, but it is not limited to these countries. Certain groups in Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, India, and other countries are also known to practice various forms of mutilation (womenshealth.gov). There are also reports of FGM in Central and South America, but little is known about the extent and prevalence of the practice there (Amnesty Intl.).

A Map of FGM prevalence from the Waris Dirie Foundation. Darker reds denote higher rates.

Ages of the victims vary by country, but the vast majority are under age 18. In Yemen, more than 75% of the females who suffer FGM are subjected before they are two weeks old (womenshealth.gov). A 2008 report from UNICEF found that, while the practice is declining in Egypt, 74% of girls aged 15-17 endured genital mutilation. Despite formal laws banning the practice in 2007, as of 2008, 33% of Egyptian mothers still want their daughters to undergo FGM. Overall, above 95% of ever-married women in Egypt are victims of this practice.

Even those who live in industrialized nations like the U.S. and U.K. are not as far removed from the practice as they believe. The African Women's Health Center at Brigham and Women's Hospital estimated in 2000 that over 225,000 girls residing in the United States would be subjected to FGM that year (equalitynow.org). The United States passed laws in 1996 banning the practice as a felony, but there are relatively few cases brought before the courts in large part due to a culture of silence surrounding the practice and the lack of a preventative law against removing a child from the U.S. in order to subject the girl to FGM in another country. As of 2010, only three states had laws against transporting children for the purposes of practicing FGM.

The United Kingdom fares no better. Despite having laws on the books since 1985 outlawing the practice, and revising these laws to address extraterritoriality (removal of a person from the country in order to commit an illegal act) in 2003, FGM is still a serious problem. Exact data on the prevalence is difficult to obtain due to the culture of silence surrounding this practice, but estimates range from 70,000 to 280,000 cases existing in the U.K. and 3,000 to 4,000 new cases happening each year (Poldermans, 2006).

A Cultural Tradition of Abuse

Although many people believe FGM or cutting is part of a religion, specifically Islam, this belief is false. Female genital cutting rituals were practiced as early as the Egyptian New Kingdom period (1550-1069 B.C.E.) and therefore predates Islam by several centuries. Furthermore, the practice affects many religious groups including Muslims, Coptic Christians, Protestants, Catholics, and various other religious groups (Fourcroy, 2006).

FGM, even in its symbolic forms, is representative of a culture's gender inequality. Likened to the now-abandoned foot-binding in China, and the practice of dowry and child marriage, FGM is a manifestation of society's control over women. This control perpetuates the inequality of the sexes and the culture of violence against women. It is so ingratiated in these societies that those who reject the practice are often ostracized or harassed (WHO, 2008).

Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation found that often the practice is part of the coming of age rituals, and considered necessary for a child to transition into a clean and marriageable woman. In some areas, the cutting includes ceremonies where gifts and recognition are given to the girl, imparting a sense of pride and ensuring the continuing cycle of violence. These same cultures cite various reasons for the practice, beyond religious influence including preserving virginity, reducing the girls sexual desire to ensure marital fidelity, and preventing sexual behaviors considered deviant or immoral. Other beliefs propagated by proponents of the practice are the enhanced sexual pleasure of the future husband, that it removes the "masculine" parts from the girl, thereby making her a more sought-after bride, and in cases of infibulations (Type 3 FGM) that it enhances beauty by achieving smoothness in the genitals.

Other misguided beliefs in FGM practicing communities liken the mutilation to purification. In some areas the popular terms for mutilation are synonymous with mutilation, such as tahara in Egypt and tahur in Sudan, or cleansing among the Bambarra in Mali known as sili-ji. Furthermore, some groups believe that a woman's clitoris is dangerous, that it can grow to enormous sizes if not excised, and that it can kill the baby during childbirth (Amnesty Intl.).

Overwhelmingly, FGM is a cultural tradition of abuse, not rooted in any scientific or psychological benefit for the victim. FGM, often done to children, prevents girls from making an independent decision about a procedure that has a lasting effect on their lives and infringes on their individual autonomy.

"The right to participate in cultural life and freedom of religion are protected by international law. However, international law stipulates that freedom to manifest one's religion of beliefs might be subject to limitations necessary to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. Therefore, social and cultural claims cannot be evoked to justify female genital mutilation." (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 18:3; UNESCO, 2001, Article 4)

Psychological and Medical Impact

Due to the highly invasive nature of the procedures (Type I, II, & III), it is no surprise that FGM can have serious and lasting medical concerns. In urban areas, this practice may be performed by a health care professional, but more than half of victims are mutilated by someone with no medical education. Proponents of the practice emphasize that serious and fatal complications are rare, but there is little accurate data on mortality rates to reinforce this assumption (Amnesty Intl.).

Short Term Complications:

• Hemorrhage (fatal blood loss has been recorded)

• Infection, up to and including sepsis

• Pain, both from the procedure and urination on the open wound for weeks after

• Severe Trauma, both physical and psychological

Long Term Health Problems:

• Chronic pain

• Urinary Tract Infections

• Pelvic Infections

• Cysts

• Excessive scar tissues and keloids

• Painful sex or Sexual Dysfunction

• Infertility

• Increased risk of pregnancy complications and infant and maternal mortality

• In Type III FGM, the need for repeated surgeries and reinfibulation after childbirth (WHO, 2012; womenshealth.gov)

The sexual effects of FGM are devastating. Effects of Female Genital Cutting on the Sexual Function of Egyptian Women found that "desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction domains were significantly higher in uncut participants [...]". Egyptian women are rarely subjected to Type III FGM and all cut participants in the study were victims of Types I & II. However, in Type III cases, believed to be between 10-15% of total FGM cases, the effects are even more disturbing. Many of these women are "opened" by their husbands in order to complete intercourse, some through penetrative sex but others surgically. Sexual relations are often painful for weeks (WHO, 2010). Often in cases of infibulations, the victim must be cut open during childbirth, deinfibulated, or risk death for both mother and child. In many societies, this is followed by reinfibulation, or re-closure of the vagina, necessitating further deinfibulation and perpetuating a painful and demeaning cycle with serious short and long term consequences.

Many of the psychological effects of FGM resemble post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including anxiety, insomnia, and depression. Although FGM is often performed in countries without adequate mental health facilities, clinical cases of psychological illness stemming from genital mutilation have been reported and personal accounts reveal feelings of terror, humiliation, and betrayal. The emotional trauma from the procedure is significant enough to continue through the woman's lifetime, and experts believe that the trauma, coupled with the shock, may be responsible for the docile and calm behavior reported from women in societies that practice FGM (Amnesty Intl.). Socially, there is enormous pressure from the family and community to continue the practice of mutilation. Failure to adhere to the cultural traditions often heaps shame on the girl and consequently her family, and may entirely prevent her from marrying. This not only deprives the girl of a possibly healthy spousal relationship but impacts the family financially as without marriage they receive no dowry (Poldermans, 2006).

Conclusion

While FGM does not affect many of us in first world nations on an individual level, as a global society we should be outraged. Girls are being raised and indoctrinated to not only accept this sexual violence but believe it is healthy and moralistic. And in doing so, they propagate this horrendous oppression to the next generation.

February 6th is the International Day of Zero-Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation, but we shouldn't wait until that day to acknowledge these depraved acts, nor should we relegate this horrifying practice to a once-a-year memorial. This practice, as well as so many other terrible human rights violations, must be fought against every single day. If you were moved at all by this article, I urge you to get involved.

Amnesty International, UNICEF, Equality Now, and many other international rights organizations are combating this vicious oppression every day, but they need the help of the global community to eradicate it fully. Educate, donate, campaign, volunteer - the opportunities to fight back against human rights violations like FGM are virtually endless. But it requires you to stand up and do something.

I will end with the testimony of Hannah Koroma, taken in Sierra Leone, by Amnesty International:

"I was genitally mutilated at the age of ten. I was told by my late grandmother that they were taking me down to the river to perform a certain ceremony, and afterwards I would be given a lot of food to eat. As an innocent child, I was led like a sheep to be slaughtered.

Once I entered the secret bush, I was taken to a very dark room and undressed. I was blindfolded and stripped naked. I was then carried by two strong women to the site for the operation. I was forced to lie flat on my back by four strong women, two holding tight to each leg. Another woman sat on my chest to prevent my upper body from moving. A piece of cloth was forced in my mouth to stop me screaming. I was then shaved.

When the operation began, I put up a big fight. The pain was terrible and unbearable. During this fight, I was badly cut and lost blood. All those who took part in the operation were half-drunk with alcohol. Others were dancing and singing, and worst of all, had stripped naked.

I was genitally mutilated with a blunt penknife.

After the operation, no one was allowed to aid me to walk. The stuff they put on my wound stank and was painful. These were terrible times for me. Each time I wanted to urinate, I was forced to stand upright. The urine would spread over the wound and would cause fresh pain all over again. Sometimes I had to force myself not to urinate for fear of the terrible pain. I was not given any anesthetic in the operation to reduce my pain, nor any antibiotics to fight against infection. Afterwards, I hemorrhaged and became anemic. This was attributed to witchcraft. I suffered for a long time from acute vaginal infections."