“Fiona Volpe would have kicked Pussy Galore’s ass,” says Adam and instantly, the wind is sucked out of the conversation. Silence prevails for several beats. Gary actually looks a little pale.

“Dude,” says Carter, incredulous. “That’s just disrespectful.”

The movie nerds are getting quarrelsome and loudly opinionated, as is often their way. Only Jake is quiet, patiently waiting his turn. As the others argue the physical and intellectual merits of their favorite Bond girls, Jake (wearing a shirt that says I AM NOT A GEEK! above fine print that reads, I’m a Level 12 Paladin) pitches toward me, eyes lowered, and says: “You know, ‘Cherry Trifle’ kinda sounds like a Bond-girl name.”

He probably lives in his mom’s basement, but is not without his charms.

Pussy Galore from Goldfinger (1964)

I’m something of a movie geek myself, but these four are the real deal: Level 12 Paladins in all things Bond. And although they have discussions exactly like this one almost every day, this one is different, because, Jake says, smiling, “Today, a girl is paying attention.”

Alas, I am hardly a Bond girl, but the bright side is, that for all their undeniable beauty, intellect and proclivity for having sex in exotic international locations with the dashing 007, they have a dreadfully low survival rate. This, Tammy M. Proctor, and author of Female Intelligence: Women and Espionage in the First World War, might argue, is one of the only ways in which these films, so near and dear to our hearts, mirror the reality of espionage.

“A lot of success in this field depends on not being flamboyant, in staying behind the scenes and being able to blend in,” says Proctor, who also is H.O. Hirt Professor of History at Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio. “Most of the women spies we know about were the ones who died, the ones who were caught.” In fact, the most famous of all, is remembered best for her fictional stage name and earlier career as an exotic dancer and courtesan.

Mother Mata

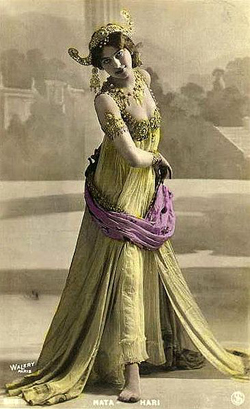

In many ways, Mata Hari is font from which the genre springs forth. Those indelible images of Hari (Dutch-born Margaretha Zelle) in her lavish headdress—and little else—may well be a pop-culture missing link; one that connects the dots to Dr. No’s Honey Ryder (Ursula Andress) and her iconic bikini, but those images are not really representative of Hari’s connection to the realm of espionage.

“The photos we all know were taken about 15 years prior to World War I,” Proctor points out. “In the ones where she was arrested, and again when executed, she’s wearing very sober clothing—looking very respectable—but none of those were published. She is 46 or so when she faces the firing squad, but [the lasting images] are of her as a much younger woman.”

Proctor explains it’s the 19th-Century myth of the angel-whore that plays out most often in the spy narratives. “Much of the popular literature about women spies after WWI was written by men—some of whom had been in espionage— who played up that very stereotype … The message is that women who spy are sexual deviants. No respectable woman would ever do this.”

Even the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. is happy to perpetuate the typecast. Proctor notes their women’s exhibit is set up to resemble a boudoir. Similarly, a 2007 exhibition about female spies lured in the masses with a slinky dame on a poster captioned “More Reasons not to Trust a Beautiful Woman.” So, have we really come a long way?

Babes In Boyland

Some might argue we have. While Bond and his ilk may have been the driving force of big-screen 60s action vehicles, on the small screen, women operatives were actually finding parity with and—gasp!—even superiority to their male counterparts. The Avengers’ groundbreaking Emma Peel (Diana Rigg) not only leveled the playing field, she raised the bar. Fashionable and fiercely intelligent, her physical prowess was more than a match for her partner, John Steed (Patrick Macnee). Get Smart’s Agent 99 (Barbara Feldon) was the brainy beauty who kept fumbling Agent 86 (Don Adams) from falling into the clutches of KAOS.

“To some degree, these movies and shows empowered women,” says Tom Lisanti, who, with Louis Paul, co-authored Film Fatales, a book chronicling a glamorous assortment of women in espionage films and television from 1962 to 1973. “For the first time, we saw female characters who weren’t screaming helplessly. They stood up to men. I think male viewers enjoyed that just as much.”

“So, can’t we just have adventure? Why the need for all the sex?” asks my friend, Alice, a psychologist, professor and self-described feminist.

“Why not?” I say. If I were a super-spy, ever on the go, burdened by the tedium of skydiving into opulent affairs in a glittering one-shouldered gown (tacking up stray locks with a jeweled scarab hair pin filled with cyanide), I’d imagine men worthy of my feminine attention would be exceedingly rare. I’d be clamoring for it.

Bond has met many matches among the women of his films, says John Cork, co-author of James Bond: The Legacy, but it doesn’t matter. “It only matters that these women are of such a rarified, exalted status that Bond must earn their affection.” That, he says, is the key. “They’re not just pretty faces. They are women whose mystery, allure and unique qualities make them desirable to men on a level far deeper.”

If James Bond is an ultimate alpha-male fantasy, the women of the franchise are his complement. “Most men are deeply intimidated by raw displays of female sexuality,” Cork offers, “and women generally experience enough testosterone ‘white noise’ in everyday life that they don’t want it becoming more overt.”

Watching women lusting after Bond, he says—“instantly aroused, eyes widening, breath deepening … It’s a fantasy, a breaking of this wall we’ve socially constructed.” Bond women, and in truth many female characters in the spy genre, do what Mata Hari did for real in the nightclubs of Berlin. They embody sexually powerful characters in ways that are acceptable. Before her demise, Mata Hari was lauded, coveted and courted by some of the most prominent men of her time.

Cork believes men not only want to feel necessary in their relationships, but also to be desired by women who are considered deeply desirable themselves. As women’s societal rights and roles have grown, power has finally made its way on to the list of traits deemed sexy and valuable. “The Bond novels and films,” Cork notes, “were there quite a bit before the rest of us.”

“Dude,” says Carter, incredulous. “That’s just disrespectful.”

The movie nerds are getting quarrelsome and loudly opinionated, as is often their way. Only Jake is quiet, patiently waiting his turn. As the others argue the physical and intellectual merits of their favorite Bond girls, Jake (wearing a shirt that says I AM NOT A GEEK! above fine print that reads, I’m a Level 12 Paladin) pitches toward me, eyes lowered, and says: “You know, ‘Cherry Trifle’ kinda sounds like a Bond-girl name.”

He probably lives in his mom’s basement, but is not without his charms.

Pussy Galore from Goldfinger (1964)

I’m something of a movie geek myself, but these four are the real deal: Level 12 Paladins in all things Bond. And although they have discussions exactly like this one almost every day, this one is different, because, Jake says, smiling, “Today, a girl is paying attention.”

Alas, I am hardly a Bond girl, but the bright side is, that for all their undeniable beauty, intellect and proclivity for having sex in exotic international locations with the dashing 007, they have a dreadfully low survival rate. This, Tammy M. Proctor, and author of Female Intelligence: Women and Espionage in the First World War, might argue, is one of the only ways in which these films, so near and dear to our hearts, mirror the reality of espionage.

“A lot of success in this field depends on not being flamboyant, in staying behind the scenes and being able to blend in,” says Proctor, who also is H.O. Hirt Professor of History at Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio. “Most of the women spies we know about were the ones who died, the ones who were caught.” In fact, the most famous of all, is remembered best for her fictional stage name and earlier career as an exotic dancer and courtesan.

Mother Mata

In many ways, Mata Hari is font from which the genre springs forth. Those indelible images of Hari (Dutch-born Margaretha Zelle) in her lavish headdress—and little else—may well be a pop-culture missing link; one that connects the dots to Dr. No’s Honey Ryder (Ursula Andress) and her iconic bikini, but those images are not really representative of Hari’s connection to the realm of espionage.

“The photos we all know were taken about 15 years prior to World War I,” Proctor points out. “In the ones where she was arrested, and again when executed, she’s wearing very sober clothing—looking very respectable—but none of those were published. She is 46 or so when she faces the firing squad, but [the lasting images] are of her as a much younger woman.”

Proctor explains it’s the 19th-Century myth of the angel-whore that plays out most often in the spy narratives. “Much of the popular literature about women spies after WWI was written by men—some of whom had been in espionage— who played up that very stereotype … The message is that women who spy are sexual deviants. No respectable woman would ever do this.”

Even the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. is happy to perpetuate the typecast. Proctor notes their women’s exhibit is set up to resemble a boudoir. Similarly, a 2007 exhibition about female spies lured in the masses with a slinky dame on a poster captioned “More Reasons not to Trust a Beautiful Woman.” So, have we really come a long way?

Babes In Boyland

Some might argue we have. While Bond and his ilk may have been the driving force of big-screen 60s action vehicles, on the small screen, women operatives were actually finding parity with and—gasp!—even superiority to their male counterparts. The Avengers’ groundbreaking Emma Peel (Diana Rigg) not only leveled the playing field, she raised the bar. Fashionable and fiercely intelligent, her physical prowess was more than a match for her partner, John Steed (Patrick Macnee). Get Smart’s Agent 99 (Barbara Feldon) was the brainy beauty who kept fumbling Agent 86 (Don Adams) from falling into the clutches of KAOS.

“To some degree, these movies and shows empowered women,” says Tom Lisanti, who, with Louis Paul, co-authored Film Fatales, a book chronicling a glamorous assortment of women in espionage films and television from 1962 to 1973. “For the first time, we saw female characters who weren’t screaming helplessly. They stood up to men. I think male viewers enjoyed that just as much.”

“So, can’t we just have adventure? Why the need for all the sex?” asks my friend, Alice, a psychologist, professor and self-described feminist.

“Why not?” I say. If I were a super-spy, ever on the go, burdened by the tedium of skydiving into opulent affairs in a glittering one-shouldered gown (tacking up stray locks with a jeweled scarab hair pin filled with cyanide), I’d imagine men worthy of my feminine attention would be exceedingly rare. I’d be clamoring for it.

Bond has met many matches among the women of his films, says John Cork, co-author of James Bond: The Legacy, but it doesn’t matter. “It only matters that these women are of such a rarified, exalted status that Bond must earn their affection.” That, he says, is the key. “They’re not just pretty faces. They are women whose mystery, allure and unique qualities make them desirable to men on a level far deeper.”

If James Bond is an ultimate alpha-male fantasy, the women of the franchise are his complement. “Most men are deeply intimidated by raw displays of female sexuality,” Cork offers, “and women generally experience enough testosterone ‘white noise’ in everyday life that they don’t want it becoming more overt.”

Watching women lusting after Bond, he says—“instantly aroused, eyes widening, breath deepening … It’s a fantasy, a breaking of this wall we’ve socially constructed.” Bond women, and in truth many female characters in the spy genre, do what Mata Hari did for real in the nightclubs of Berlin. They embody sexually powerful characters in ways that are acceptable. Before her demise, Mata Hari was lauded, coveted and courted by some of the most prominent men of her time.

Cork believes men not only want to feel necessary in their relationships, but also to be desired by women who are considered deeply desirable themselves. As women’s societal rights and roles have grown, power has finally made its way on to the list of traits deemed sexy and valuable. “The Bond novels and films,” Cork notes, “were there quite a bit before the rest of us.”

Nobody puts the Bond girls in the corner, at least when Cherry pays tribute to them. A rich sampling of retro and curves!