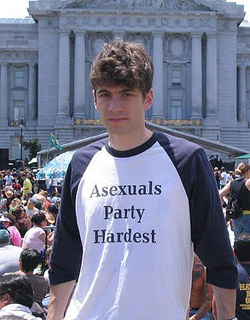

Jay’s goal is to create open honest dialogue about asexuality among both sexual and asexual people. He has brought his message to mainstream America on The View, Montel, ABC Primetime, CNN, Fox News and more.

Jay reminds us that unlike celibacy, which is a choice, asexuality is a sexual orientation. Asexual people have needs for intimacy and relationships like anyone else, but those relationships just look a little different.

Being asexual gives him a different perspective on masculinity and male sexuality. This slight distance, allows him to acknowledge things that may be hard to see ourselves. Here, he dissects male friendships, masculine role models and male power.

As an asexual person, you must have an interesting take on the messages that men receive from this culture about their sexuality.

I think there’s an interesting cultural struggle going on, at least judging by the advertising that’s targeting my demographic right now. I think there’s this sense that masculinity, as it’s traditionally articulated, is really problematic, so masculinity isn’t something that we seriously address. Also, it’s not something that’s presented to us in a serious way. In [current] culture, it’s presented to us almost comically.

What effect does masculinity not being taken seriously have?

So, my friends and I, when we act traditionally masculine, we are both performing and making fun of masculinity. But we aren’t examining it, and we end up expressing our gender that way. It’s not, I’ve thought a lot of masculinity and other forms of gender expression; it’s the way I relate to my masculinity is by making fun of masculinity. And other than that, I don’t really know how to deal with it.

Has masculinity has become too self-deprecating?

I don’t even know … It’s this image of masculinity that we know is problematic, but is also empowering. And we wanna access some of that power, even though we know it’s problematic. So you can’t do it blatantly, it becomes: I’m gonna do it by kind of making fun of it, and I get some of that empowerment and some of that identity without having to take it seriously.

What are some of the messages men soak up about their sexuality?

That our sexuality is problematic and destructive. I think that’s the message. I think that culturally there aren’t enough symbols of non-destructive sexuality for men to really adopt.

Are there any masculine symbols you look up to?

The most defining factor of my masculinity, happened was when I was in high school. There was the group of popular girls, the ones that ran everything socially. My freshman year, some critical mass of them started realizing they were gay. Then two of them had a falling out and there was this cascading outing process that happened over the course of a week. A couple of the ringleaders wound up becoming butch. That became my image of what was cool and what was powerful and what was respected.

Popular teenage lesbians formed your masculinity? That is different.

They were able to embrace masculinity without a lot of the history of oppression I have associated with it. And they were able to take some of the assertiveness and the cultural icons of masculinity, and use them to create this world that jived way more with my sense of social justice.

I also gravitated to that because, as a young asexual kid that was the safest place for me to find intimacy. I knew if I became close with a straight girl, there was this whole question of her sexuality directed at me, which I wasn’t ready to deal with—the same problem with a gay guy. And if I became close to a straight guy, there were rules about emotional expression and affection, it wasn’t that kind of relationship where we could actively explore being close in the way I wanted to. But if I became really close with lesbian a lot of that was fixed.

Another potentially destructive message men get is that they need to be hypersexual—the whole “Men think about sex 10,000 times a day” thing.

I think where that message leads men is, if they have a desire for emotional connection, that’s something that they’re going to experience in sex. I’ve definitely had conversations with a lot of guys that start out expressing what they’ve label as “sexuality,” but if I kind of prod, there’s a lot of other emotional stuff that’s under that. And it may or may not have anything to do with sexuality, they just may not have another language set for expressing it.

As someone who is asexual, I’d imagine the hypersexual issue is one you’ve had to deal with.

Being asexual growing up I mean, that is clearly something I really struggled with. I had to really go out of my way to prove I wasn’t in that paradigm. Like, if I was engaged in a conversation with someone and I was interested in them, I had to prove that wasn’t about sexuality, but some other aspects of them. And since then I’ve realized that expressing sexual intimacy with someone and expressing non-sexual intimacy with someone are not actually that different.

A lot of asexual people’s need for intimacy is filled by friendship. Can you talk about friendship from a guy’s perspective?

I think that in general, my male friends, especially straight male friends, are less likely to see their friends and communities as a vital component of their lives. They do tend to be emotionally intelligent and understand what they want. But my straight male friends don’t sit down and think about their communities, and say, Okay, who are my friends right now? Do I have friends that I want? And what’s the status of this friendship They tend to value friends a lot, but they don’t tend to be as proactive about friends.

It sometimes seems women take their friendships more seriously than guys do, but is that true?

There’s still a different standard in terms of guys being affectionate in friendships versus women. I also think that intimacy happens in affection, it happens in how people express emotions to one another, and it also happens in shared passion. And I think, in male-male relationships, men have more permission to engage in shared passion as intimacy. It’s, We’re gonna go on a road trip, We’ll start a band… some activity that’s gonna bring us closer together.

When you come out to people as asexual, are men’s responses different than women’s?

The men are way less likely to want to talk about it. Some will ask questions almost clinically or academically. And they’ll be apologetic about it, like, “Wow, I’m sorry I just really don’t understand and I’m really curious like, how does this work for you? Like, what does this look like?” Women and some queer men will want to engage me about it and use that as a way to open up a discussion that allows them to examine their own sex, maybe in a new interesting way.

So, where are you today with your gender role as an asexual guy, and your masculinity?

It’s tricky. So much of how we express our sexuality is gender. And we are still trying to figure out what the expression of asexuality looks like.

A lot of the images of empowerment for men are tied up with sexuality. Learning how to have an empowered gender identity without sexuality is really tricky. It took looking at parts of me that were more masculine and what they meant in a nonsexual way, how I think about having any kind of desires.

Where does that come up for you?

Professional identity tends to be very gendered. In my job, if I have things I desire I will tap into that masculinity. I’ve also found that in my media presentation of asexuality, I tend to be masculine. There is a really strong pre-existing social image that asexuality is disempowering. But I’ve found that people respond to masculinity, that it makes asexuality more interesting to them because it’s harder for them to dismiss.

Why is that?

Sexuality and masculinity and power are linked. And if I perform masculinity when I’m talking about asexuality, it gives people the sense that even though I’m asexual, I still have something like masculine sexual power. It positions us to be respected. But when I’m trying to get them to understand the complexities of how asexuality works, I’ll use a lot of feminine sexual language, and that energy. I’ll use the phrase “asexual slut” which is a female sexualized word. To kind of allude to the fact that asexual desire exists in a really complicated form. I think it’s way more embodied in female sexuality that in male sexuality.

Absolutely. You are just playing with gender-roles.

Yes. It’s fun.

Jay reminds us that unlike celibacy, which is a choice, asexuality is a sexual orientation. Asexual people have needs for intimacy and relationships like anyone else, but those relationships just look a little different.

Being asexual gives him a different perspective on masculinity and male sexuality. This slight distance, allows him to acknowledge things that may be hard to see ourselves. Here, he dissects male friendships, masculine role models and male power.

As an asexual person, you must have an interesting take on the messages that men receive from this culture about their sexuality.

I think there’s an interesting cultural struggle going on, at least judging by the advertising that’s targeting my demographic right now. I think there’s this sense that masculinity, as it’s traditionally articulated, is really problematic, so masculinity isn’t something that we seriously address. Also, it’s not something that’s presented to us in a serious way. In [current] culture, it’s presented to us almost comically.

What effect does masculinity not being taken seriously have?

So, my friends and I, when we act traditionally masculine, we are both performing and making fun of masculinity. But we aren’t examining it, and we end up expressing our gender that way. It’s not, I’ve thought a lot of masculinity and other forms of gender expression; it’s the way I relate to my masculinity is by making fun of masculinity. And other than that, I don’t really know how to deal with it.

Has masculinity has become too self-deprecating?

I don’t even know … It’s this image of masculinity that we know is problematic, but is also empowering. And we wanna access some of that power, even though we know it’s problematic. So you can’t do it blatantly, it becomes: I’m gonna do it by kind of making fun of it, and I get some of that empowerment and some of that identity without having to take it seriously.

What are some of the messages men soak up about their sexuality?

That our sexuality is problematic and destructive. I think that’s the message. I think that culturally there aren’t enough symbols of non-destructive sexuality for men to really adopt.

Are there any masculine symbols you look up to?

The most defining factor of my masculinity, happened was when I was in high school. There was the group of popular girls, the ones that ran everything socially. My freshman year, some critical mass of them started realizing they were gay. Then two of them had a falling out and there was this cascading outing process that happened over the course of a week. A couple of the ringleaders wound up becoming butch. That became my image of what was cool and what was powerful and what was respected.

Popular teenage lesbians formed your masculinity? That is different.

They were able to embrace masculinity without a lot of the history of oppression I have associated with it. And they were able to take some of the assertiveness and the cultural icons of masculinity, and use them to create this world that jived way more with my sense of social justice.

I also gravitated to that because, as a young asexual kid that was the safest place for me to find intimacy. I knew if I became close with a straight girl, there was this whole question of her sexuality directed at me, which I wasn’t ready to deal with—the same problem with a gay guy. And if I became close to a straight guy, there were rules about emotional expression and affection, it wasn’t that kind of relationship where we could actively explore being close in the way I wanted to. But if I became really close with lesbian a lot of that was fixed.

Another potentially destructive message men get is that they need to be hypersexual—the whole “Men think about sex 10,000 times a day” thing.

I think where that message leads men is, if they have a desire for emotional connection, that’s something that they’re going to experience in sex. I’ve definitely had conversations with a lot of guys that start out expressing what they’ve label as “sexuality,” but if I kind of prod, there’s a lot of other emotional stuff that’s under that. And it may or may not have anything to do with sexuality, they just may not have another language set for expressing it.

As someone who is asexual, I’d imagine the hypersexual issue is one you’ve had to deal with.

Being asexual growing up I mean, that is clearly something I really struggled with. I had to really go out of my way to prove I wasn’t in that paradigm. Like, if I was engaged in a conversation with someone and I was interested in them, I had to prove that wasn’t about sexuality, but some other aspects of them. And since then I’ve realized that expressing sexual intimacy with someone and expressing non-sexual intimacy with someone are not actually that different.

A lot of asexual people’s need for intimacy is filled by friendship. Can you talk about friendship from a guy’s perspective?

I think that in general, my male friends, especially straight male friends, are less likely to see their friends and communities as a vital component of their lives. They do tend to be emotionally intelligent and understand what they want. But my straight male friends don’t sit down and think about their communities, and say, Okay, who are my friends right now? Do I have friends that I want? And what’s the status of this friendship They tend to value friends a lot, but they don’t tend to be as proactive about friends.

It sometimes seems women take their friendships more seriously than guys do, but is that true?

There’s still a different standard in terms of guys being affectionate in friendships versus women. I also think that intimacy happens in affection, it happens in how people express emotions to one another, and it also happens in shared passion. And I think, in male-male relationships, men have more permission to engage in shared passion as intimacy. It’s, We’re gonna go on a road trip, We’ll start a band… some activity that’s gonna bring us closer together.

When you come out to people as asexual, are men’s responses different than women’s?

The men are way less likely to want to talk about it. Some will ask questions almost clinically or academically. And they’ll be apologetic about it, like, “Wow, I’m sorry I just really don’t understand and I’m really curious like, how does this work for you? Like, what does this look like?” Women and some queer men will want to engage me about it and use that as a way to open up a discussion that allows them to examine their own sex, maybe in a new interesting way.

So, where are you today with your gender role as an asexual guy, and your masculinity?

It’s tricky. So much of how we express our sexuality is gender. And we are still trying to figure out what the expression of asexuality looks like.

A lot of the images of empowerment for men are tied up with sexuality. Learning how to have an empowered gender identity without sexuality is really tricky. It took looking at parts of me that were more masculine and what they meant in a nonsexual way, how I think about having any kind of desires.

Where does that come up for you?

Professional identity tends to be very gendered. In my job, if I have things I desire I will tap into that masculinity. I’ve also found that in my media presentation of asexuality, I tend to be masculine. There is a really strong pre-existing social image that asexuality is disempowering. But I’ve found that people respond to masculinity, that it makes asexuality more interesting to them because it’s harder for them to dismiss.

Why is that?

Sexuality and masculinity and power are linked. And if I perform masculinity when I’m talking about asexuality, it gives people the sense that even though I’m asexual, I still have something like masculine sexual power. It positions us to be respected. But when I’m trying to get them to understand the complexities of how asexuality works, I’ll use a lot of feminine sexual language, and that energy. I’ll use the phrase “asexual slut” which is a female sexualized word. To kind of allude to the fact that asexual desire exists in a really complicated form. I think it’s way more embodied in female sexuality that in male sexuality.

Absolutely. You are just playing with gender-roles.

Yes. It’s fun.

Comments