“The Hairpin Drop Heard Round the World”

1969. It was a year unlike any other...stop us if you’ve heard this one before. Right—you’ve read the books, seen the infomercials, bought the “Now That’s What I Call Hippy Music!” 12-CD boxed set, and thoroughly pwned the T-shirt (retrograde fashion of course). That being said, it really was an age unto itself—an age of taking absolutely nothing for granted.

It was, to borrow a phrase, “the summer of ’69.” John Lennon kicked off the month of June by recording “Give Peace a Chance”. Meanwhile, half a world away, Vietnam was in full orange bloom. It’s easy to take freedom for granted, especially in this day and age—but let’s review a little history: It had only been five years earlier that LBJ signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a full 99 years after Congress had passed the Thirteenth Amendment. It had only been 45 years since American women had been given the right to vote.

But if you were gay, things weren’t quite so peachy. Civil rights did not apply to homosexuality; every state in the union possessed and vigorously enforced anti-gay laws, to the extent that the slightest public display of same-sex unity could lead to incarceration, or, worse—a one-way trip to the nearest sanitarium (homosexuality was still considered a “sociopathic personality disturbance” by the American Psychiatric Association).

And then there was “the hairpin drop heard round the world,” on June 27, 1969, at a gay bar in Greenwich Village called The Stonewall Inn. Back in the day, police raids on any number of establishments, especially those with mob connections, were de rigueur. And if said establishment catered to a gay and lesbian clientele, then all bets were off. Usually these raids went down as a simple matter of course, meeting with little if any resistance. But on this particular night, all that changed—violently. Rashomon and Rosa Parks

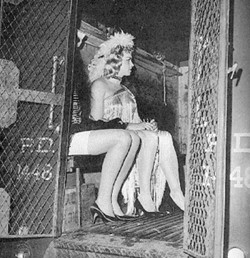

Sometimes the raids were carried out under pretenses of liquor law violations. Some nights there was no pretense whatsoever. Either way, anyone looking “too gay” usually found themselves hauled off in a paddy wagon. Their names were published, which usually resulted in them losing their jobs. The lucky ones (i.e., those who weren’t in drag or otherwise “deviant”—in these instances, even gay men got to experience a little bit of white male privilege) made a hasty beeline toward the rear exit without being hauled off to the hoosegow.

And on June 27, 1969, alcohol—or its illegal sale—was the charge du jour. The plainclothesmen and uniformed officers began their ritualistic duty of arresting the bar’s employees, harassing its clientele, and depositing them out onto Christopher Street with all the aplomb of, well, cops from the 1960s. But the story quickly went off-script on this night. Some attribute what was to follow to the death five days previously of Judy Garland. Others, possibly the more pragmatic, attribute it to simply having had enough.

It was, to borrow a phrase, “the summer of ’69.” John Lennon kicked off the month of June by recording “Give Peace a Chance”. Meanwhile, half a world away, Vietnam was in full orange bloom. It’s easy to take freedom for granted, especially in this day and age—but let’s review a little history: It had only been five years earlier that LBJ signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a full 99 years after Congress had passed the Thirteenth Amendment. It had only been 45 years since American women had been given the right to vote.

But if you were gay, things weren’t quite so peachy. Civil rights did not apply to homosexuality; every state in the union possessed and vigorously enforced anti-gay laws, to the extent that the slightest public display of same-sex unity could lead to incarceration, or, worse—a one-way trip to the nearest sanitarium (homosexuality was still considered a “sociopathic personality disturbance” by the American Psychiatric Association).

And then there was “the hairpin drop heard round the world,” on June 27, 1969, at a gay bar in Greenwich Village called The Stonewall Inn. Back in the day, police raids on any number of establishments, especially those with mob connections, were de rigueur. And if said establishment catered to a gay and lesbian clientele, then all bets were off. Usually these raids went down as a simple matter of course, meeting with little if any resistance. But on this particular night, all that changed—violently. Rashomon and Rosa Parks

Sometimes the raids were carried out under pretenses of liquor law violations. Some nights there was no pretense whatsoever. Either way, anyone looking “too gay” usually found themselves hauled off in a paddy wagon. Their names were published, which usually resulted in them losing their jobs. The lucky ones (i.e., those who weren’t in drag or otherwise “deviant”—in these instances, even gay men got to experience a little bit of white male privilege) made a hasty beeline toward the rear exit without being hauled off to the hoosegow.

And on June 27, 1969, alcohol—or its illegal sale—was the charge du jour. The plainclothesmen and uniformed officers began their ritualistic duty of arresting the bar’s employees, harassing its clientele, and depositing them out onto Christopher Street with all the aplomb of, well, cops from the 1960s. But the story quickly went off-script on this night. Some attribute what was to follow to the death five days previously of Judy Garland. Others, possibly the more pragmatic, attribute it to simply having had enough.

Comments