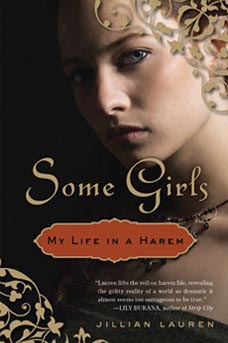

In her New York Times bestselling memoir Some Girls: My Life in a Harem (Plume), Jillian Lauren takes us from her childhood in New Jersey, with adoptive parents who didn’t quite get her, to bohemian New York, where some artsy types did. She works as a stripper, which leads her to escorting and before long hops a plane to join a gaggle of girls at the palace of Prince Jefri of Brunei. Her job is basically to look hot, while being treated to shopping sprees, soirees and, yes, the occasional roll in the hay (plus one blowjob for his brother, the Sultan of Brunei). Her passion for the prince means the job is more than a job, and some of the book’s most moving passages illuminate the emotional ups and downs of being constantly compared to other women, even within the confines of the harem, hoping to be chosen.

Lauren now lives in Los Angeles with her husband, Weezer bassist Scott Shriner, and their son, Tariku. Fresh from her book tour, which took her around the country, not to mention The Howard Stern Show and The View, Lauren emailed us her thoughts on life-changing tattoos, personal transformation and whether “hooker” is a dirty word.

How long after your experiences in Brunei did you come to write Some Girls, and why was it important for you to do so?

Eighteen years passed before I was able to tell this story. It took that long to be ready, from both a craft standpoint and an emotional standpoint, to do the story justice. I think it’s important for women to be truthful about their lives, particularly women on the fringes of society, who often keep silent because we’re led to believe that our stories are something to be ashamed of. We let our stories be told by others, usually men, and we wind up repeatedly being the bodies left behind by serial killers or the hookers with the hearts of gold. I wanted to tell my own story: how I became a sex worker and what it did to my life and my dreams. I wanted to portray the complexity of the experience and to present an emotional journey that I believe will be familiar to many women, even those to whom the events of the narrative may seem outrageous.

Why did you choose that title?

[TheRolling Stones'] Some Girls is one of my favorite albums of all time. The refrain “some girls” kept coming popping up rhythmically in my sentences as I was writing, probably because the song altered my cellular structure at some point in my teenage years. I chose it as the title because the song is so raw and politically incorrect and I believe that the book is of the same tradition. I also chose it for the obvious, literal connection.

Your emotional involvement with the prince was very compelling. You seemed very street smart, and knew you were taking on a job as a sex worker, yet you also fell for him. Did that surprise you? Was it harder to separate your emotions with him than other clients?

There was a lot of grey area in my experience in Brunei. It was a job, but it also wasn’t. Technically I was just a guest. There was no contract. There was no “payment,” only gifts. But then again, I wasn’t free to come and go from the palace, or to do as I pleased with my evenings, so it wasn’t exactly a vacation either. The Brunei harem was an extremely unusual situation. I did fall for the prince.

Part of the reason I wrote the book was to portray the complexity of the situation. I wanted to challenge the impulse people have to oversimplify. I think sex work is always a field with some grey area. You’re trafficking in desire, and that’s never clean or easy.

How did your time as a sex worker affect your personal love and sex life? Do you feel it was useful to you?

I feel that everything in my life has been useful to me in some way. My years as a sex worker reinforced some deep damage that it has taken years to try to undo. I’m still healing. But all of it has been a lesson in compassion for others and for myself.

My personal test for a good book is whether it makes me cry. Yours did. There’s a toughness and a brashness and, most especially, a self-assuredness about your attitude toward sex work that softens when you write about your birth mother, your relationships, and your abortion. That tension between tough and tender is a running theme throughout the book. Do you feel that the toughness was an act?

I think all of it was real to some extent. I was tough. I was brave—and I was a giant softie at heart at the same time. I was a confused teenager who had no idea who I was, but still thought I knew it all.

You write about your tattoos and tattoo culture in such a way that your life almost seems to start at that moment. What drew you to that world, and which is your favorite tattoo?

Thanks for mentioning the tattoos! People get so swept up in the exoticism of the harem story that no one ever mentions the fact that in the book I got a tattoo on my vagina for god’s sake.

I decided to get a tattoo when the tattoo gods announced themselves to me. That’s how Eddy Deutsche once described it to me and I thought—that’s exactly it. I have a mystical connection to tattooing. My favorite used to be the Tibetan Dakini I have on my shoulder, although I just got two koi with their tails intertwined in honor of my son, who is a Pisces, so I guess that tops all.

When you were on The View, Barbara Walters called you a “hooker” and some people took offense to that, calling it pejorative. Do you think we’ve evolved enough as a culture so that “hooker/prostitute/sex worker” are just descriptive words rather than slurs?

Well, It didn’t bother me half as much as it bothered all of my friends. That’s what the book is about after all. I don’t think Barbara Walters had some personal vendetta; I think she was just using strong words to create a captivating story. I’m a storyteller too, so I can appreciate that.

You have a novel, Pretty, coming out in 2011. Can you give us a hint about that?

Pretty centers around Bebe Baker, who is a self-described ex-everything: ex-Christian, ex-stripper, ex-drug addict, ex-pretty girl. A year after surviving a horrific car accident that killed her boyfriend, she serves out a self-imposed sentence at a halfway house, while attempting to complete her last two weeks of vocational-rehab cosmetology school. Pretty is about trying to find faith in a world of rampant diagnoses, over-medication, compulsive eating, and acrylic nails.

Your current married/mom life seems very different from the life of nonstop adventure and rebellion of your youth. How does the Jillian Lauren of 2010 relate to the Jillian Lauren in the book?

The real lessons for me were learned as I looked back and reflected. I was able to discover a love for both myself and for the other people who shared my story. I looked at pictures of myself from that time and I said, What was so wrong with me? Why did I hate myself so much? I was beautiful. I was hopeful. I was brave. I was adorable. I can see it now clear as day, but I couldn’t see it then. The story is about struggling to love yourself and learning to forgive yourself.

Jillian Lauren will be reading July 15, 7:30 to 10 pm, at Rachel Kramer Bussel's In The Flesh Reading Series.