When you get a group of expats together in India, the conversation will always find its way to two things: lamenting the absence of Mexican food and Bollywood. I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had with Desis and Westerners alike about how terrible and ubiquitous the world’s most popular cinema is in India.

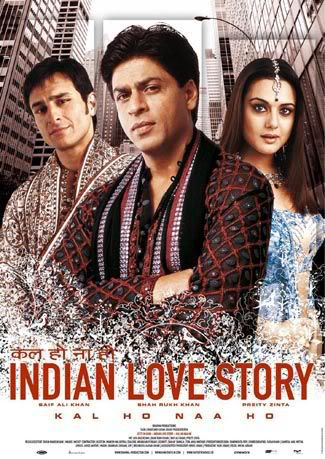

Walk 10 steps, and you’ll have passed the face of Shahrukh Khan at least four times on ads for HP Compaq computers, Sunfeast Snacky biscuits, Lux soap, and the latest blockbuster. I learned my lesson the hard way about the amount of reverence that must be given at all times to these stars-cum-gods when a friend was conveying to me the latest gossip about Mr. Khan.

“Is that the one whose skin looks like boot leather?” I jokingly asked, and received a perturbed look in response. How dare I insult the sexiest man in Bollywood? One of the most powerful men in India! Oops, my bad.

When my friend recovered from the shock he said, “You know, for a lot of queer Indian men, Shahrukh is a gay icon.”

Now it was my turn to be taken aback. “Come again?”

“Well, aside from the rumors that he and Karan Johar had a fling, Shahrukh embodies the queer sensibility of Bollywood to a lot of gay men. All that homoerotic dosti (friendship) and campy song and dance? It’s so gay, darling.”

My friend had a point. Until then, I’d read the on-screen same-sex interactions through a homosocial lens, shrugging off the intimate touches and melodramatic exchanges as representations of Indian gender norms that allow for such closeness in a way that American gender norms do not.

It’s not uncommon to see teenage boys holding hands or lazing around in each other’s laps, and girls walking home from school arm in arm with regularity. In fact, this same friend told me that he feels more at ease as a gay man in India because it is socially acceptable for him to be openly affectionate with his boyfriend in public. He is able to hide in plain sight.

Not that he really has to hide at all. He’s an upper class Bengali man whose family both accepts and supports his sexual orientation, so in many ways the typical rules don’t apply to him. On top of that, the rules are rapidly changing, and Bollywood is one powerful entity that is propelling such change. In his essay “Queer Bollywood, or ‘I’m the Player, You’re the Naive One,’” Thomas Waugh says that Bollywood creates “narrative worlds in which the borders around and within homosociality have always been naively and uninhibitedly ambiguous.”

“Hindi cinema is already queer,” queer filmmaker Ishita Srivastava explained when I recently interviewed her about her short documentary Desigirls. “The exaggerated acting style, the song and dance routines, the emotionality that all characters embrace.”

Srivastava believes the potential impact of Bollywood on the acceptance of gay men and lesbians in South Asian communities may be less than immediate, but profound in the long-term. “We have a long way to go to break down the very rigid standards of heteronormativity that are at the core of our films,” she says. “I think the only way to break these down and still appeal to the mass public is with baby steps—steps that introduce concepts like gay and lesbian into the minds of people who otherwise go about their entire lives totally oblivious, even though their brothers, sisters, children, or uncles might be living these lives right in front of their eyes. By introducing these concepts and inciting dialogue and discussion, these films make an intervention, for sure.”

Srivastava is a newcomer to a growing group of South Asian diasporic filmmakers that started to break ground in the early ’90s when the likes of Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta and Pratibha Parmar came on the international cinema scene. Their films explored taboo aspects of Indian sexuality, including homosexuality, with a freedom that wasn’t widely permitted in their homeland, but they carved a space for themselves across geographic boundaries and so gained the respect of their peers.

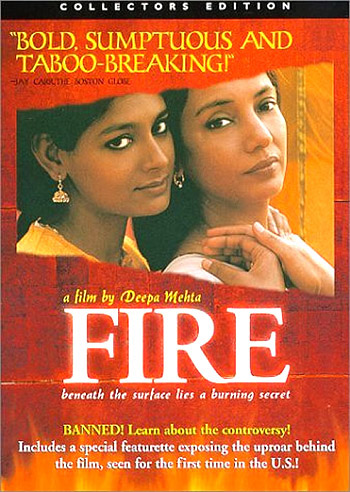

The 1996 worldwide release of Deepa Mehta’s Fire was the first notable mainstream foray for a film depicting a lesbian relationship between Indian women. The award-winning film met with controversy shortly after it debuted in India because a powerful group of right-wing Hindus claimed its queer content was “immoral” and “not a part of Indian history or culture.” They attacked moviegoers and destroyed cinema halls in order to prevent the film from being seen. Just 14 years later, movies by diasporic filmmakers, like Shamim Sarif's [https://www.icantthinkstraight-themovie.com/ |I Can’t Think Straight, are being released across India with hardly a murmur because Fire notoriously paved the way.

Another film that is often cited as breaking barriers is 2008’s wildly popular Dostana, in which Bollywood stars John Abraham and Abhishek Bachchan play two straight men who pretend to be gay in order to live with a gorgeous girl, played by starlet Priyanka Chopra. Although the film is (rightfully) critiqued for its problematic stereotypical portrayal of gay men and a boy-on-boy kiss as punishment for bad behavior, the characters’ feigned sexuality is introduced in the film as a way to make the two men seem respectable to Chopra’s aunt who would not have sullied her niece’s reputation by allowing her to live with two heterosexual men—not even in Miami, where the film is set.

Despite its drawbacks, Srivastava chose the name of her own film as an homage to Johar’s attempt to open the closet door for mainstream India. (“Desi Girl” was one of the hit songs from Dostana.)

“The title of my film is definitely a shout out to the queer subtext in Karan Johar’s films,” says Srivastava. “There has been a lot of criticism of his portrayal of two pseudo-gay men, and the actual gay men he shows in the film are quite ridiculous in the way they crystallize the stereotype of an effeminate, camp, gay man as the only way a gay man can be. That said, I think films like Dostana are important because they bring the concept of being gay or lesbian—something that, while pervasive, is still rarely articulated in popular Indian culture—to the fore.

“Big male stars like Abhishek Bachchan and John Abraham playing openly gay men is not something that would have happened 10 years ago, and given the wide reach of Hindi films, it is quite a step in the right direction.”

While having homosexuality as the central plot device in a Bollywood film is obviously transgressive, what about more nuanced queer representations? Are those even acknowledged by a straight audience—and does it even matter?

When Bollywood goes gay, the Western media starts salivating over the same old ethnocentric story: the backward country is pushing forward, but the truth is that the conversation isn’t that simple and sometimes it can be surprising. Exchanges in global media, the repeal of discriminatory laws, and diasporic films’ gain in popularity worldwide are all affecting the increased acceptance of queers in India in ways that are similar and different from the U.S. Countries develop in their own unique way given their particular culture and history, and India is no different.

The great thing about art is that authorship is in the hands of both the creator and the viewer; if you read something into a film and that’s not how the creator intended it, it doesn’t matter because the meaning is still there for you. A normative behavior may be read as straight by the average Desi, and queered by a cultural outsider or a gay man who wants to see himself popularly represented. In this way, queerness is both visible and invisible in Bollywood—it all depends on who is watching the film.

Walk 10 steps, and you’ll have passed the face of Shahrukh Khan at least four times on ads for HP Compaq computers, Sunfeast Snacky biscuits, Lux soap, and the latest blockbuster. I learned my lesson the hard way about the amount of reverence that must be given at all times to these stars-cum-gods when a friend was conveying to me the latest gossip about Mr. Khan.

“Is that the one whose skin looks like boot leather?” I jokingly asked, and received a perturbed look in response. How dare I insult the sexiest man in Bollywood? One of the most powerful men in India! Oops, my bad.

When my friend recovered from the shock he said, “You know, for a lot of queer Indian men, Shahrukh is a gay icon.”

Now it was my turn to be taken aback. “Come again?”

“Well, aside from the rumors that he and Karan Johar had a fling, Shahrukh embodies the queer sensibility of Bollywood to a lot of gay men. All that homoerotic dosti (friendship) and campy song and dance? It’s so gay, darling.”

My friend had a point. Until then, I’d read the on-screen same-sex interactions through a homosocial lens, shrugging off the intimate touches and melodramatic exchanges as representations of Indian gender norms that allow for such closeness in a way that American gender norms do not.

It’s not uncommon to see teenage boys holding hands or lazing around in each other’s laps, and girls walking home from school arm in arm with regularity. In fact, this same friend told me that he feels more at ease as a gay man in India because it is socially acceptable for him to be openly affectionate with his boyfriend in public. He is able to hide in plain sight.

Not that he really has to hide at all. He’s an upper class Bengali man whose family both accepts and supports his sexual orientation, so in many ways the typical rules don’t apply to him. On top of that, the rules are rapidly changing, and Bollywood is one powerful entity that is propelling such change. In his essay “Queer Bollywood, or ‘I’m the Player, You’re the Naive One,’” Thomas Waugh says that Bollywood creates “narrative worlds in which the borders around and within homosociality have always been naively and uninhibitedly ambiguous.”

“Hindi cinema is already queer,” queer filmmaker Ishita Srivastava explained when I recently interviewed her about her short documentary Desigirls. “The exaggerated acting style, the song and dance routines, the emotionality that all characters embrace.”

Srivastava believes the potential impact of Bollywood on the acceptance of gay men and lesbians in South Asian communities may be less than immediate, but profound in the long-term. “We have a long way to go to break down the very rigid standards of heteronormativity that are at the core of our films,” she says. “I think the only way to break these down and still appeal to the mass public is with baby steps—steps that introduce concepts like gay and lesbian into the minds of people who otherwise go about their entire lives totally oblivious, even though their brothers, sisters, children, or uncles might be living these lives right in front of their eyes. By introducing these concepts and inciting dialogue and discussion, these films make an intervention, for sure.”

Srivastava is a newcomer to a growing group of South Asian diasporic filmmakers that started to break ground in the early ’90s when the likes of Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta and Pratibha Parmar came on the international cinema scene. Their films explored taboo aspects of Indian sexuality, including homosexuality, with a freedom that wasn’t widely permitted in their homeland, but they carved a space for themselves across geographic boundaries and so gained the respect of their peers.

The 1996 worldwide release of Deepa Mehta’s Fire was the first notable mainstream foray for a film depicting a lesbian relationship between Indian women. The award-winning film met with controversy shortly after it debuted in India because a powerful group of right-wing Hindus claimed its queer content was “immoral” and “not a part of Indian history or culture.” They attacked moviegoers and destroyed cinema halls in order to prevent the film from being seen. Just 14 years later, movies by diasporic filmmakers, like Shamim Sarif's [https://www.icantthinkstraight-themovie.com/ |I Can’t Think Straight, are being released across India with hardly a murmur because Fire notoriously paved the way.

Another film that is often cited as breaking barriers is 2008’s wildly popular Dostana, in which Bollywood stars John Abraham and Abhishek Bachchan play two straight men who pretend to be gay in order to live with a gorgeous girl, played by starlet Priyanka Chopra. Although the film is (rightfully) critiqued for its problematic stereotypical portrayal of gay men and a boy-on-boy kiss as punishment for bad behavior, the characters’ feigned sexuality is introduced in the film as a way to make the two men seem respectable to Chopra’s aunt who would not have sullied her niece’s reputation by allowing her to live with two heterosexual men—not even in Miami, where the film is set.

Despite its drawbacks, Srivastava chose the name of her own film as an homage to Johar’s attempt to open the closet door for mainstream India. (“Desi Girl” was one of the hit songs from Dostana.)

“The title of my film is definitely a shout out to the queer subtext in Karan Johar’s films,” says Srivastava. “There has been a lot of criticism of his portrayal of two pseudo-gay men, and the actual gay men he shows in the film are quite ridiculous in the way they crystallize the stereotype of an effeminate, camp, gay man as the only way a gay man can be. That said, I think films like Dostana are important because they bring the concept of being gay or lesbian—something that, while pervasive, is still rarely articulated in popular Indian culture—to the fore.

“Big male stars like Abhishek Bachchan and John Abraham playing openly gay men is not something that would have happened 10 years ago, and given the wide reach of Hindi films, it is quite a step in the right direction.”

While having homosexuality as the central plot device in a Bollywood film is obviously transgressive, what about more nuanced queer representations? Are those even acknowledged by a straight audience—and does it even matter?

When Bollywood goes gay, the Western media starts salivating over the same old ethnocentric story: the backward country is pushing forward, but the truth is that the conversation isn’t that simple and sometimes it can be surprising. Exchanges in global media, the repeal of discriminatory laws, and diasporic films’ gain in popularity worldwide are all affecting the increased acceptance of queers in India in ways that are similar and different from the U.S. Countries develop in their own unique way given their particular culture and history, and India is no different.

The great thing about art is that authorship is in the hands of both the creator and the viewer; if you read something into a film and that’s not how the creator intended it, it doesn’t matter because the meaning is still there for you. A normative behavior may be read as straight by the average Desi, and queered by a cultural outsider or a gay man who wants to see himself popularly represented. In this way, queerness is both visible and invisible in Bollywood—it all depends on who is watching the film.

Comments