Birth of the Underground (Gee, That Didn’t Take Long)

While sexual content in the medium’s mainstream has historically been subdued, often to the point of being subliminal, voices from the medium’s underground let loose with explicit, mind-blowing sexual content, limited only by the creators’ gleefully vivid imaginations. An impressive feat for a medium that languished for decades under the most restrictive censorship scheme ever to shackle an art form. For your dining and dancing pleasure, we proudly present the genesis of this dichotomy, along with the cheap thrills and surreal carnal pleasures that could only come from what’s been traditionally perceived as the most disreputable art form in America.

In 1933, Funnies on Parade was published. It was a cheap collection of reprints from daily comic strips assembled into the format we’ve come to recognize as the comic book, published to be used as a giveaway item by Proctor and Gamble. A humble beginning that birthed a medium that would delight and subvert for the next 76 years.

Sex crept into the formative medium long before 1933, though. Anonymous cartoonists cranked out eight page booklets called Tijuana Bibles from the 1920’s to the 1960’s. These sleazy little numbers placed beloved characters from the funny pages into sexual situations never envisioned by their creators. If readers wanted to see Blondie servicing Dagwood with inventive and acrobatic vigor, the Tijuana Bibles had them covered. They represented the first recognizable comics underground and demonstrated that an eager audience existed for material in the comic format that transcended the tame and wholesome.

has been a profound influence to legions of artists from World War II to the present day, with his lush, almost photo-realistic renderings of seductive glamour girls, along with his humorous captions which grounded his work in the time-honored cartooning tradition. His artwork for Esquire and Playboy remain the pinnacle of the pin-up aesthetic.

Lateral moves from comics to magazines were frequent, particularly as the comics medium cemented its place as an American pop art institution. Dan DeCarlo, best known for establishing Archie Comics’ in-house art style, was a frequent contributor to Argosy. His clean, simple linework were unmistakable, and he brought a spicier version of Archie’s brand of humor to his magazine work, endearing him to Argosy’s readership. Bill Ward was another Golden Age icon who made the transition, albeit with more explicit carnality than most of his peers exhibited. His comics’ work on the military adventure Blackhawk and Torchy, his slinky, flirtatious ingénue were hits with G.I.’s serving on the front lines. Ward finally found his true bliss with his pornographic work, becoming a fixture in Juggs, Leg Show, and Club.

Hugh Hefner had a keen appreciation of satire and the comics medium alike, prompting him to recruit a stellar array of cartoonists to grace Playboy’s pages, as well as bringing onboard two veterans from EC’s glory days: Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder. Together, they created Little Annie Fanny, a loveable, clueless innocent who blundered into sexually compromising situations in every installment. The strip was gorgeously illustrated and scathingly funny, quickly becoming one of Playboy’s most popular features.

In his relentless quest to slavishly imitate Playboy, Bob Guccione commissioned Oh, Wicked Wanda! for Penthouse. Written by Frederic Mullally with Ron Embleton handling the artwork, the series followed Wanda, a die-hard, man-hating lesbian on her darkly comic, globe-trotting escapades. Embleton’s work on children’s features in the UK, including education comics and Disney’s UK titles was highly regarded; he raised quite a few eyebrows when he got the chance to set his imagination loose with Wanda.

It’s a synergy that’s worked awfully well. Magazines get stellar work from comics’ top talent while their readership get hip to the comics medium’s artistic potential. With the Good Girl Art aesthetic alive and thriving, it’s a marriage that promises to be happy and healthy for years to come.

]

The Golden Age of Comics (Sexual Subtext Included At No Extra Charge)

The Golden Age of comics (ca. 1938 to 1950) was the period that saw comics’ most explosive growth and the introduction of what became the medium’s staple: the superhero. Publishers still saw them as kiddie fare and marketed them as such. Still, artists found ways to finesse titillating content into their work.

For provocative sensual shenanigans, you couldn’t top Wonder Woman. Overt bondage situations on the covers and interior art along with hints of lesbianism made the Amazing Amazon’s titles the most subversive titles of The Golden Age. Raised by the Amazons on Paradise Island (where no man could ever set foot), she grew to womanhood in a culture where her sister Amazons entertained themselves with spirited wrestling matches and bondage play.

Psychologist William Moulton Martson, Wonder Woman’s creator, was an early champion of feminism, convinced that the ideal society was one where men freely and joyfully submitted to women. Humanity would enjoy a Utopia free from war and fascism, a compelling ideal at a time when Hitler was carving up Europe. If his Amazon demi-goddess could subtly sway her impressionable young readers in that direction, so much the better.

Even Superman got into the act. Sort of. Joe Shuster, co-creator of the comic book icon, self-published titillating booklets entitled Nights of Horror in the 1950’s. Characters that bore an uncanny resemblance to Superman and Lois Lane enjoyed sado-masochistic frolics with whips, hot pokers, and other implements guaranteed to bring the pain. Shuster’s explorations of his darker fantasies were another precursor of a full-fledged underground comics movement – there was an audience for this stuff even if they had to go to the black market for it. Shuster’s porntastic etchings have recently been re-released in the book Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-Creator Joe Shuster.

Seducing the Innocent

The popularity of superhero comics waned after World War II and publishers offered the most diverse range of content the medium would enjoy for decades. Westerns, crime comics, science-fiction titles, and horror mags stood out on the racks; genres that lent themselves to more racy and sensational content that had more appeal to their creators and readers than yet another formula batch of stories featuring musclemen in tights.

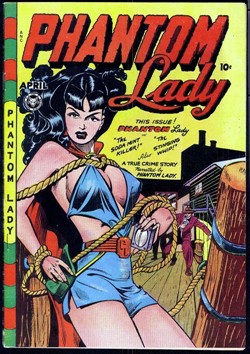

This became the heyday of Good Girl Art, a style inspired by pin-up art and the steamy covers of the era’s pulps and cheap paperbacks. Bill Ward and Harvey Kurtzman came to fame in this period and went on to create comic strips for Club and Playboy respectively. These comics exemplify how sexed-up comics were able to become during the time and comics featuring Good Girl Art continue to command a premium price from collectors. While there was still no overt sexual content, the unbridled cheesecake on display was provocative, eye catching, and the finest work rivaled any contemporary pin-up art. Matt Baker, one of the very few African-American comic artists of the period and certainly the most celebrated one, was a Good Girl Art luminary; his Phantom Lady covers provide a shining example of “headlights covers”, artwork that prominently features exploitative emphasis on women’s breasts.

By the end of the 1940’s, comics had become impressively lurid; some of the titles produced during this era boggle the imagination. A measly dime would treat youngsters to Teen-Age Dope Slaves or Reform School Girl!, a title that offered, “The graphic story of boys and girls running wild in the violence-ridden slums of today!” Parents were becoming increasingly uneasy about the titles available to their children and the content of the era’s horror comics were on the verge of creating a furor.

William Gaines’ EC imprint boasted titles such as The Haunt of Fear and Tales From the Crypt; titles that were tremendously influential to contemporary writers and filmmakers including Stephen King and George A. Romero. Boasting a stable of high-octane talent like Wally Wood, Basil Wolverton, and Frank Frazetta, EC comics were disreputable, nasty, and wonderfully subversive fun; comics that were destined to horrify parents, representing a comics underground hiding in plain sight. Covers were adorned with rotting zombies, freshly severed heads, and junkies writhing in agonizing withdrawl throes. The interiors delivered what the covers promised. “Foul Play” concluded with a baseball diamond adorned with a hapless player’s intestines and viscera. Adapted works came from acclaimed writers like Ray Bradbury and EC’s original stories were reknowned for wickedly mordant humor and twist endings that were genuinely jolting. Many of the best would be adapted decades later in HBO’s Tales from the Crypt. While most publishers were conscientiously kid-friendly, EC provided the edgiest fare on the spinner rack.

So it should’ve come as no surprise to the industry when the backlash came, and boy, did the whip ever come down with a vengeance.

Enter Dr. Wertham

In 1954, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent was published. A scathing broadside against the comics industry, Wertham postulated that reading comic books stunted developing young minds and led youngsters down the slippery slope to juvenile delinquency and moral decay. Wertham’s sloppy research was chiefly anecdotal; by interviewing juvenile offenders and learning that they read comic books, he formed the cause/effect relationship that reading comics leads children into criminal behavior. That didn’t matter; his book roused the ire of parents and educators and Wertham did a fine job at culling and reprinting particularly violent and salacious comic book panels to pour gasoline into the fire and Seduction became an influential best-seller.

Riding the crest of his fame, Wertham was invited to testify before Senator Estes Kefauver’s Subcommittee on Juvenile Deliquency in 1954, which was investigating the role of comic books in promoting juvenile delinquency. Gaines also accepted an invitation to testify, though it would’ve been better if he’d sat that one out. During one memorable exchange, Gaines proclaimed that he only published works in good taste. Kefauver displayed the cover to Crime SuspenStories #22 which depicted an axe-wielding murderer carrying a woman’s severed head.

Senator Estes Kefauver: This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman's head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

Gaines: Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it, and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

That one really didn’t fly very well with the Subcommittee or the parents’ groups that read the transcript.

The Subcommittee ultimately found that there was no direct connection; however, they strongly “suggested” that publishers tone down their act. Translation: Do it yourselves or we’ll do it for you. Between that threat and the bad publicity generated by Seduction and the hearings, the publishers opted to censor themselves.

They created The Comics Code Authority in 1954 to fend off the government and skirt financial ruin. No more graphic violence, no behavior that could even remotely be construed as glorifying criminal activity, and the restrictions on sexual content were draconian. Sample regulations: “Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.” “Suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture is unacceptable.” “Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.” Goodbye Good Girl Art, goodbye horror titles, and goodbye EC comics. It would take the counterculture to spawn the artistic movement that would elevate the comics medium beyond children’s picture books.

The Undergrounds – Comics Get Their Groove On

1960’s counterculture spawned a new wave of creators who were in the first generation to grow up immersed in the medium, inspired not only by the comics of their youths, but also by the pop art, rock music and drug culture of their day. It was time for creators like Robert Crumb, Vaughn Bode, and Gilbert Shelton to make their marks on the medium. They weren’t interested in grinding out superhero and funny animal books for mainstream publishers; they need venues for their unique visions that the Comics Code couldn’t touch.

Comics veteran Wally Wood gave an inkling of what was to come with his Sally Forth strip. Introduced in 1968’s Military News, Sally was a voluptuous commando with a penchant for winding up nude during her missions. The feature began as a conventional adventure feature with nudity and sexuality, but as alcoholism and depression took its toll on Wood, Sally’s escapades descended into hardcore pornography.

In 1968, Robert Crumb self-published Zap Comix #1 which bore the legend, “Fair Warning: For Adult Intellectuals Only”. No form of expression was taboo in Zap and artists including S. Clay Wilson and Spain Rodriguez would contribute to future issues, cementing their status in underground comics. Zap’s stories, especially the work of Crumb and Rodriguez were taken to task for their misogyny. Crumb’s female characters were typically nothing better than sperm receptacles and Rodriguez’ work was loaded with horrific violence directed against women. Still, the work was also remarkably intelligent and subversive, taking Mad Magazine’s sensibility (which many of the creators had read growing up) and adapting it to counterculture mores and their own freewheeling artistic ideals.

Other notable underground pioneers include Vaughn Bode, creator of Cheech Wizard, the perpetually horny, self-proclaimed Cartoon Messiah. Cheech’s hobbies were trying to bed voluptuous women and giving a swift kick in the nuts to anybody who irritated him. Happily for comedy affecionados, the underground sensibility didn’t preclude slapstick. Spain Rodriguez had arguably the most bleak and hard-edged vision of the early underground creators, often drawing his material from his days running with biker gangs. Works such as Mean Bitch Thrills, were every bit as explicit as anything Crumb conceived and often perceived as vehemently misogynistic.

Independents’ Day

As the “Me Generation” of the 1970’s supplanted the counterculture, the undergrounds’ visibility and vitality declined. Experiencing an increasing number of busts for carrying drug paraphernalia, many head shops closed their doors, leaving undergrounds with fewer outlets to reach their readers. Concurrently, a growing number of specialty shops opened in the United States devotedly primarily to comic books, serving a rapidly growing collectors’ market. Talent that might’ve been drawn into the undergrounds earlier was being pulled into a new independent comics boom.

The indie publishers were inspired by self-publishers like Dave Sim, whose Cerebus the Aardvark enjoyed a healthy fan base, as well as genre magazine Heavy Metal, which presented science-fiction and fantasy enlivened with copious amounts of graphic sex and violence brought to readers by acclaimed European talents such as Moebius and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Art Spiegelman’s Raw, debuting in 1980, provided a transition from the undergrounds to the independents. While publishing material geared to an adult readership with mature storylines and frank depictions of sensuality, with Raw, Spiegelman was more interested in taking the medium to a new artistic pinnacle than pushing the envelope of sex and violence. Raw attracted the talents of established international stars such as Jose Munoz and Tardi as well as underground comics veterans including Bill Griffith and Robert Crumb. These publications demonstrated that there was an adult comics audience hungry for mature genre storytelling and the new comic shops allowed the indies to bypass the traditional comic outlets to present offerings not tainted by The Comics Code to the public.

These publishers initially bypassed the genre’s primary staple of superheroics. Pacific Comics launched in 1981 with Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers, a science fiction series created by legendary artist Jack Kirby. Dave Stevens breathtakingly revived the Good Girl Art tradition with his lushly rendered Airboy. For unbridled nudity and gore, Bruce Jones’ Alien Worlds and Twisted Tales were the Pacific titles that delivered it in spades. Both were EC homages, that recreated the publisher’s beloved storytelling style, albeit with content that was far more graphic than anything Gaines had ever released.

First Comics graced the world with Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg, a dystopian science-fiction saga featuring an unemployed porn star turned corporate cop. Chaykin’s work was far more subdued than the undergrounds, but the title still had much more provocative sexual content than the industry’s giants, Marvel and DC, would ever allow in their pages.

The direct market’s ascendancy was also responsible for the phenomenon of comic book superstardom. Chris Claremont and John Byrne were among the first; their work on Marvel’s red hot X-Men title regularly sold hundreds of thousands of copies. Marvel was forced to sweeten the pot to keep them happy and continue selling truckloads of X-Men books to the fans that salivated over every issue. They modified the traditional work-for-hire system, in which creators were paid a flat page rate and nothing more, regardless of how well their titles sold and DC followed suit to avoid defections of their top talent to their arch-rival. Royalties and other incentives were introduced; finally, the talent was getting the fiscal rewards that were long overdue. Unhappily, this new model prompted creators for the mainstream publishers and independents alike to lunge for the money. Artistically integrity became an endangered species. Trying to come up with a new sexed-up mutant book that would sell a million copies was now the name of the game.

Gary Groth’s Fantagraphics was the exception to this rule. Consistently publishing titles with content that was mature in every sense of the word, Fantagraphics has provided a home to titles that have become indie favorites. Love and Rockets, a long-running dramatic series created by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, is a prime example. This critical hit features intertwined narratives that explore the lives and loves of Latin Americans as well as chicano life in the U.S.

The independents were now a driving force The Big Two couldn’t ignore; they’d crashed the party and were here to stay. In our next thrilling installment, we’ll explore how Marvel and DC tried to co-opt the indies’ sensibilities, admire their successes, laugh at their failures, and explore how the presentation of sexuality in their titles has both matured and degenerated, from the mid-1980’s to the present day. Stay tuned because you know you don’t want to miss the epic tale of triumph, tragedy, and mawkish stupidity to come.