Controversy follows international award-winning writer Bruce Benderson as the author continues raising hell on his freewheeling, dangerous literary journey into the dark worlds of self, identity, and sexuality.

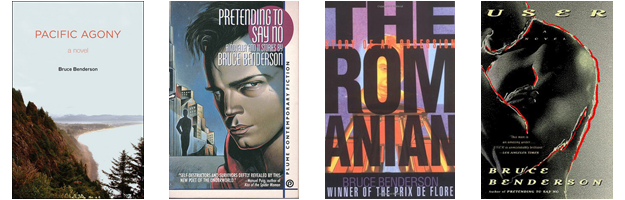

Winner of the prestigious French literary prize, the Prix de Flore for his erotic memoir, The Romanian, Benderson brings a unique sensibility and stance to every subject he encounters, whether fiction or non-fiction. Currently, his provocative novel, Pacific Agony, published by Semiotext(e)/MIT, stirred the critics up with his prickly observations on society, place, race and class.

Benderson loves creating outside the box, defying all convention and all expectation. “Benderson is a true heir of D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Paul Bowles, the Bohemian bourgeois,” wrote Catherine Texier, author of Panic Blood and Breakup.

Born to Jewish parents of Russian descent, Benderson was always attracted to unorthodox and unusual things. “I even have a few memories from kindergarten in which my response to things wasn’t what it was supposed to be,” he says. “I always liked the colors I wasn’t supposed to like, the books that no one my age was supposed to be interested in, the people that others thought were uncool.”

His liberal, progressive-minded father wanted his son to be a free thinker unfettered by societal restraints. “My father went out of his way to get Miller’s Tropic of Cancer when it was banned in our city, followed by Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Naked Lunch. I learned a lot about sex by reading Peyton Place before that.”

Probably American readers were shocked by Benderson’s complete immersion into the shadowy Sodom of the old Times Square sex world, rubbing shoulders with hustlers, prostitutes, druggies, trannies and a sinister criminal element. “My interest in that world began in 1985, after a friend loaned me the novel Saul’s Book, which was about a middle-aged con artist of Jewish descent and his Puerto Rican hustler lover. I was mesmerized by the world it described and went in search of it in Times Square.”

Most of the stories in Pretending to Say No (1990) and his breakthrough novel, User (1994) used the sex industry of that gritty location. Asked by a magazine scribe, he replied: “I’m a middle class person encountering the street of the street. The more I stay outside that world, the more I’m a voyeur. But the more I enter it, the more I participate. What I write about becomes more and more true.”

Like John Rechy and Hubert Selby’s work on sexual outlaws, mainstream critics noted Benderson’s skill in finding the humanity in those attending hustler bars, peep shows and porn theaters. Others blasted his art being wasted on the “underclass” and the poor.

“I would not describe myself as siding with the underclass,” Benderson says. “A lot of my writing is a comedy of manners that shows what happens when middle class people encounter people outside their class and the absurdity that results. I think people outside his own class can be incredible inspiring for a certain type of middle class artist, such as myself.”

“I also learned a lot from the poor, from whom I had been protected as I grew in a white, middle class home,” he continued. “The media had always portrayed the world of the poor in a very narrow way. But actually, they were as various and as vital as the people of any world.”

With Benderson’s award-winning memoir, The Romanian: Story of an Obsession, peers and pundits were astonished with the raw sexual fireworks of a writer in lust with a hustler.

“Maybe it feels that way because of how frank and self-revealing I was, even when being so wasn’t so flattering to me,” Benderson notes. That’s what most critics, especially in France, mentioned: that they were amazed at the extent to which I was willing to reveal myself. The Romanian certainly isn’t a discreet work.”

A first-rate journalist and essayist, Benderson has written on the plight of squatters in New York Times Magazine, the rigors of boxing for Village Voice, and other articles on film, book, and culture for American and international publications. He scored high marks for his remarkable book-length essays, Toward the New Degeneracy (1997) and Sex and Isolation (2007), with the themes of the sex consumers of rich and poor in a lustful environment and the Internet’s role in sexuality.

Wearing another hat as an excellent translator of controversial French work, Benderson has made the cream of Gallic sensuality available for American markets, such as Viriginie Despentes’ Baise Moi (2003), Nelly Arcan’s Whore (2004), Tony Duvert’s Diary of an Innocent (2010), and volumes by Robbe-Grillet, Gregoire Bouillier, Martin Page, and Benoit Duteurtre.

It was Benderson, who revealed the maker of the 1971 cult film, Pink Narcissus, a landmark in erotic male images. His book, James Bidgood (1999) was deemed an instant classic. “I made up my mind to find out and researching leads until I discovered Bidgood, who was living in a small apartment in Greenwich Village with his cats, and all the slides from his marvelous photography work were sitting in a rumpled paper bag at the back of his closet. I was overjoyed.”

All writers, worth their salt, have style, courage and a flair for unpredictability. Benderson can be very unpredictable. A high point in his career was ghost-writing Celine Dion: My Story, My Dream (2000), which was a surprise to most of the writer’s followers. “I forgot which contact hooked me up with the gig,” he confesses. “But it paid well, and I was living in Romania with my obsession, very much in need of money, so I took the job.”

Known for his sexual prowess, Benderson is reputed to have racked many conquests during his time as a “super-stud.” He jokes: “I wish someone would spread the word at this point. You may be alluding to the fact I’ve cited numbers in the four-figure range when I talked about my sex life. That really isn’t so unusual for my generation of gay men. A lot of us went to the baths more than once a week, and had a dozen or so contacts each visit. Just do the math.”

Who do you read when you want an erotic thrill, locally or internationally? “Does anyone read for an erotic thrill these days, when erotic thrills are so much more easily available in the visual media, like film? But I can’t think of any films I’ve used for that purpose, either.”

Currently, Benderson writes a monthly column in French for the magazine, “Tetu.” He’s also written an upcoming book about the future where biology and technology intersects for a French publisher. He divides his time between New York and Paris.

What are you working on now? “Just stuff that will get me paid,” Benderson says. “Nothing too creative.”

Winner of the prestigious French literary prize, the Prix de Flore for his erotic memoir, The Romanian, Benderson brings a unique sensibility and stance to every subject he encounters, whether fiction or non-fiction. Currently, his provocative novel, Pacific Agony, published by Semiotext(e)/MIT, stirred the critics up with his prickly observations on society, place, race and class.

Benderson loves creating outside the box, defying all convention and all expectation. “Benderson is a true heir of D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Paul Bowles, the Bohemian bourgeois,” wrote Catherine Texier, author of Panic Blood and Breakup.

Born to Jewish parents of Russian descent, Benderson was always attracted to unorthodox and unusual things. “I even have a few memories from kindergarten in which my response to things wasn’t what it was supposed to be,” he says. “I always liked the colors I wasn’t supposed to like, the books that no one my age was supposed to be interested in, the people that others thought were uncool.”

His liberal, progressive-minded father wanted his son to be a free thinker unfettered by societal restraints. “My father went out of his way to get Miller’s Tropic of Cancer when it was banned in our city, followed by Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Naked Lunch. I learned a lot about sex by reading Peyton Place before that.”

Probably American readers were shocked by Benderson’s complete immersion into the shadowy Sodom of the old Times Square sex world, rubbing shoulders with hustlers, prostitutes, druggies, trannies and a sinister criminal element. “My interest in that world began in 1985, after a friend loaned me the novel Saul’s Book, which was about a middle-aged con artist of Jewish descent and his Puerto Rican hustler lover. I was mesmerized by the world it described and went in search of it in Times Square.”

Most of the stories in Pretending to Say No (1990) and his breakthrough novel, User (1994) used the sex industry of that gritty location. Asked by a magazine scribe, he replied: “I’m a middle class person encountering the street of the street. The more I stay outside that world, the more I’m a voyeur. But the more I enter it, the more I participate. What I write about becomes more and more true.”

Like John Rechy and Hubert Selby’s work on sexual outlaws, mainstream critics noted Benderson’s skill in finding the humanity in those attending hustler bars, peep shows and porn theaters. Others blasted his art being wasted on the “underclass” and the poor.

“I would not describe myself as siding with the underclass,” Benderson says. “A lot of my writing is a comedy of manners that shows what happens when middle class people encounter people outside their class and the absurdity that results. I think people outside his own class can be incredible inspiring for a certain type of middle class artist, such as myself.”

“I also learned a lot from the poor, from whom I had been protected as I grew in a white, middle class home,” he continued. “The media had always portrayed the world of the poor in a very narrow way. But actually, they were as various and as vital as the people of any world.”

With Benderson’s award-winning memoir, The Romanian: Story of an Obsession, peers and pundits were astonished with the raw sexual fireworks of a writer in lust with a hustler.

“Maybe it feels that way because of how frank and self-revealing I was, even when being so wasn’t so flattering to me,” Benderson notes. That’s what most critics, especially in France, mentioned: that they were amazed at the extent to which I was willing to reveal myself. The Romanian certainly isn’t a discreet work.”

A first-rate journalist and essayist, Benderson has written on the plight of squatters in New York Times Magazine, the rigors of boxing for Village Voice, and other articles on film, book, and culture for American and international publications. He scored high marks for his remarkable book-length essays, Toward the New Degeneracy (1997) and Sex and Isolation (2007), with the themes of the sex consumers of rich and poor in a lustful environment and the Internet’s role in sexuality.

Wearing another hat as an excellent translator of controversial French work, Benderson has made the cream of Gallic sensuality available for American markets, such as Viriginie Despentes’ Baise Moi (2003), Nelly Arcan’s Whore (2004), Tony Duvert’s Diary of an Innocent (2010), and volumes by Robbe-Grillet, Gregoire Bouillier, Martin Page, and Benoit Duteurtre.

It was Benderson, who revealed the maker of the 1971 cult film, Pink Narcissus, a landmark in erotic male images. His book, James Bidgood (1999) was deemed an instant classic. “I made up my mind to find out and researching leads until I discovered Bidgood, who was living in a small apartment in Greenwich Village with his cats, and all the slides from his marvelous photography work were sitting in a rumpled paper bag at the back of his closet. I was overjoyed.”

All writers, worth their salt, have style, courage and a flair for unpredictability. Benderson can be very unpredictable. A high point in his career was ghost-writing Celine Dion: My Story, My Dream (2000), which was a surprise to most of the writer’s followers. “I forgot which contact hooked me up with the gig,” he confesses. “But it paid well, and I was living in Romania with my obsession, very much in need of money, so I took the job.”

Known for his sexual prowess, Benderson is reputed to have racked many conquests during his time as a “super-stud.” He jokes: “I wish someone would spread the word at this point. You may be alluding to the fact I’ve cited numbers in the four-figure range when I talked about my sex life. That really isn’t so unusual for my generation of gay men. A lot of us went to the baths more than once a week, and had a dozen or so contacts each visit. Just do the math.”

Who do you read when you want an erotic thrill, locally or internationally? “Does anyone read for an erotic thrill these days, when erotic thrills are so much more easily available in the visual media, like film? But I can’t think of any films I’ve used for that purpose, either.”

Currently, Benderson writes a monthly column in French for the magazine, “Tetu.” He’s also written an upcoming book about the future where biology and technology intersects for a French publisher. He divides his time between New York and Paris.

What are you working on now? “Just stuff that will get me paid,” Benderson says. “Nothing too creative.”

An excellent review, Cole. I really enjoy your writing style with each piece I read.

What an intersting man (and family).