Poetry & Other Dirty Sexy Truths

“Do I speak now only about issues of sexuality or do I look at the issues that go hand in hand with being a black gay man: racism, economic injustice, crime rates in the communities. How do I make my work speak to and make those connections?”—Essex Hemphill

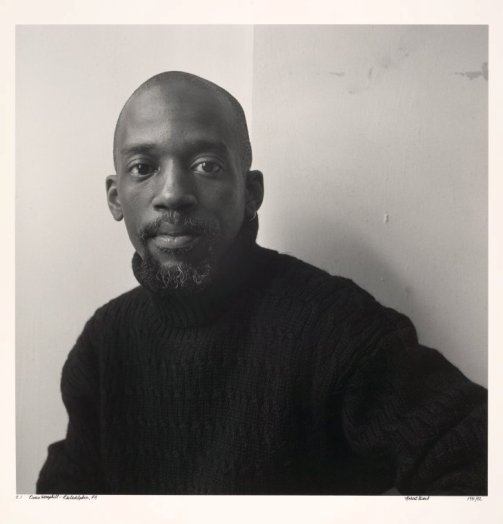

Poet: Essex Hemphill (1957-1995)

Born in Chicago, raised in Southeast Washington D.C., Essex Hemphill became one of the best known black gay poets of his generation. He started writing poetry at 14, but captured national attention with his work in the groundbreaking anthology, In The Life: A Black Gay Anthology, befriending the anthology’s editor Joseph Beam in the process.

Another AIDS casualty, Philadelphia activist/editor Joseph Beam died before finishing Brother to Brother (the sequel to In The Life). Beam’s mother, Dorothy, found Hemphill’s name repeated among her son’s papers and recruited him to finish the anthology. Hemphill dedicated himself to the project, at one point even moving in with the Beam family to complete it. In 1991, Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men was published by Alyson Books and won a Lambda Literary Award.

In 1992, Hemphill’s book Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry won the National Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual New Author Award. In his essay “Loyalty,” he wrote: “The black homosexual is hard pressed to gain audience among his heterosexual brothers; even if he is more talented. He is inhibited by his silence or his admissions. This is what the race has depended on in being able to erase homosexuality from our recorded history... It is not enough to tell us that one was a brilliant poet, scientist, educator, or rebel. Whom did he love? It makes a difference. I can’t become a whole man simply on what is fed to me: watered-down versions of black life in America. I need the truth to be told, I will have something pure to emulate, a reason to remain loyal.”

Hemphill received literary fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the D.C. Commission for the Arts. He taught a course on black gay identity at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC. In 1993, he was a visiting scholar at The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities. Hemphill’s poetry appeared in numerous magazines, newspaper and journals including Obsidian, Black Scholar, Callaloo, Painted Bride Quarterly, and Essence. His poems were also included in the anthologies Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time (1986) and Life Sentences: Writers, Artists and AIDS (1993), as well as featured in the award-winning documentaries: Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied and Issac Julien’s Looking for Langston.

Essex Hemphill’s poetry is passionate and accessible; lyrical and archival—the truth of black gay men’s experience, an honest record. A record that includes angelic drag queens, disapproving aunts, cynical idealism and a refusal to be erased or whited-out of history.

Songs & Secrets

Ofra Haza (1957–2000)

Israeli singer and actress, Ofra Haza, popularized “world beat” music, a fusion of modern Pop music with traditional melodies and instruments.

A true Cinderella story: Haza was born the youngest of nine children. Following her death, Prime Minister Ehud Barak commented, “Ofra emerged from the Hatikvah slums to reach the peak of Israeli culture. She has left a mark on us all.”

Dubbed “the Madonna of the East,” Haza earned platinum and gold records, Grammy nomination and topped musical charts (and MTV video rotations) in Asia, Europe and the USA during the ’80 and ’90s. She performed with musical stars such as Paula Abdul, Michael Jackson, Iggy Pop, Whitney Houston, and Sinéad O’Connor, and also sang on the soundtracks of Colors (1988), Dick Tracy (1990), Wild Orchid (1990), Queen Margot (1994), The Prince of Egypt (1998), The Governess (1998) and American Psycho (2000). Haza’s songs continue to be re-released, re-mixed and sampled after her death, and were featured in the video game Grand Theft Auto (2005).

Ofra Haza and Iggy Pop perform: "Daw Da Hiya," a song of forbidden love.

The singing career Haza began at the age of 12, ended at with her passing at age 42 of AIDS-related multiple organ failure. Investigation into her death showed that she avoided treatment out of fear that her AIDS would become public knowledge.

“It brings us back to the beginning of the epidemic with the near-demonization and stigmatization of a disease that actually we are dealing with much better,” said Dr. Zvi Bentwich, head of the AIDS Center at Kaplan Hospital in Rehovot. “And in this unfortunate case, it appears that Ofra Haza almost died of the embarrassment, from the terrible fear to reveal her illness.”

Public outcry pointed an accusatory finger at the husband of the star with a reputation for clean living. Doron Ashkenazi married the superstar in 1997. The couple had no children together. Several complaints were filed with the police, accusing Ashkenazi of not informing Haza that he was HIV positive, but he was never arrested. In April 2000, Ashkenazi died of a cocaine overdose and the investigation was closed.

A newspaper report of Haza’s death sparked international debate over whether the paper had breached journalistic ethics and violated the privacy of the singer, or whether it had “done a public service by refusing to treat AIDS as an illness whose name cannot be spoken.”