Poetry & Other Dirty Sexy Truths

“Do I speak now only about issues of sexuality or do I look at the issues that go hand in hand with being a black gay man: racism, economic injustice, crime rates in the communities. How do I make my work speak to and make those connections?”—Essex Hemphill

Poet: Essex Hemphill (1957-1995)

Born in Chicago, raised in Southeast Washington D.C., Essex Hemphill became one of the best known black gay poets of his generation. He started writing poetry at 14, but captured national attention with his work in the groundbreaking anthology, In The Life: A Black Gay Anthology, befriending the anthology’s editor Joseph Beam in the process.

Another AIDS casualty, Philadelphia activist/editor Joseph Beam died before finishing Brother to Brother (the sequel to In The Life). Beam’s mother, Dorothy, found Hemphill’s name repeated among her son’s papers and recruited him to finish the anthology. Hemphill dedicated himself to the project, at one point even moving in with the Beam family to complete it. In 1991, Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men was published by Alyson Books and won a Lambda Literary Award.

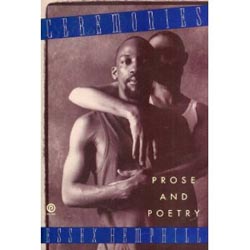

In 1992, Hemphill’s book Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry won the National Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual New Author Award. In his essay “Loyalty,” he wrote: “The black homosexual is hard pressed to gain audience among his heterosexual brothers; even if he is more talented. He is inhibited by his silence or his admissions. This is what the race has depended on in being able to erase homosexuality from our recorded history... It is not enough to tell us that one was a brilliant poet, scientist, educator, or rebel. Whom did he love? It makes a difference. I can’t become a whole man simply on what is fed to me: watered-down versions of black life in America. I need the truth to be told, I will have something pure to emulate, a reason to remain loyal.”

Hemphill received literary fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the D.C. Commission for the Arts. He taught a course on black gay identity at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC. In 1993, he was a visiting scholar at The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities. Hemphill’s poetry appeared in numerous magazines, newspaper and journals including Obsidian, Black Scholar, Callaloo, Painted Bride Quarterly, and Essence. His poems were also included in the anthologies Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time (1986) and Life Sentences: Writers, Artists and AIDS (1993), as well as featured in the award-winning documentaries: Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied and Issac Julien’s Looking for Langston.

Essex Hemphill’s poetry is passionate and accessible; lyrical and archival—the truth of black gay men’s experience, an honest record. A record that includes angelic drag queens, disapproving aunts, cynical idealism and a refusal to be erased or whited-out of history.

Poet: Essex Hemphill (1957-1995)

Born in Chicago, raised in Southeast Washington D.C., Essex Hemphill became one of the best known black gay poets of his generation. He started writing poetry at 14, but captured national attention with his work in the groundbreaking anthology, In The Life: A Black Gay Anthology, befriending the anthology’s editor Joseph Beam in the process.

Another AIDS casualty, Philadelphia activist/editor Joseph Beam died before finishing Brother to Brother (the sequel to In The Life). Beam’s mother, Dorothy, found Hemphill’s name repeated among her son’s papers and recruited him to finish the anthology. Hemphill dedicated himself to the project, at one point even moving in with the Beam family to complete it. In 1991, Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men was published by Alyson Books and won a Lambda Literary Award.

In 1992, Hemphill’s book Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry won the National Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual New Author Award. In his essay “Loyalty,” he wrote: “The black homosexual is hard pressed to gain audience among his heterosexual brothers; even if he is more talented. He is inhibited by his silence or his admissions. This is what the race has depended on in being able to erase homosexuality from our recorded history... It is not enough to tell us that one was a brilliant poet, scientist, educator, or rebel. Whom did he love? It makes a difference. I can’t become a whole man simply on what is fed to me: watered-down versions of black life in America. I need the truth to be told, I will have something pure to emulate, a reason to remain loyal.”

Hemphill received literary fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the D.C. Commission for the Arts. He taught a course on black gay identity at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC. In 1993, he was a visiting scholar at The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities. Hemphill’s poetry appeared in numerous magazines, newspaper and journals including Obsidian, Black Scholar, Callaloo, Painted Bride Quarterly, and Essence. His poems were also included in the anthologies Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time (1986) and Life Sentences: Writers, Artists and AIDS (1993), as well as featured in the award-winning documentaries: Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied and Issac Julien’s Looking for Langston.

Essex Hemphill’s poetry is passionate and accessible; lyrical and archival—the truth of black gay men’s experience, an honest record. A record that includes angelic drag queens, disapproving aunts, cynical idealism and a refusal to be erased or whited-out of history.

Comments