Maybe I’ve watched too much AbFab, but David Jay is not at all like I expected a fashion photographer to be. There was no sweetie-darling, no gossip and no name-dropping during our phone interview…in fact, at one point he fretted a bit that he might have made some of his subjects look “too beautiful,” a concept I have never heard in the world of fashion.

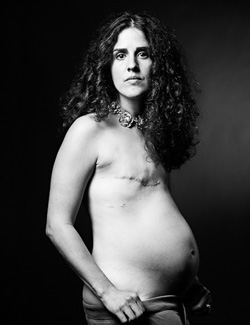

But David Jay isn’t a fashion industry caricature. Five years ago, when he was living in Australia a close friend of his was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 29 and had a mastectomy within two weeks of diagnosis. It was the genesis of a series of photographs that would literally change the way we see breast cancer: The Scar Project. Jay, a fashion photographer by trade, began taking pictures of breast cancer survivors, their nude or semi-nude bodies, their scars, their truth. The resulting photos are breath taking in their honesty, a reminder that we might be culturally more aware of breast cancer than ever but many of us have never really seen it.

The Scar Project had already been turned into a book and recently it became a documentary Baring it All, which premiered on the Style Network in July. The film follows four subjects through different stages of treatment and recovery. Director Patricia Zagarella, who Jay calls “an amazing filmmaker,” and the Style Network, “did it right,” he says. The doc “is a very, very accurate portrayal of The Scar Project,” though he agrees that the medium presents a different experience than the gallery setting. The photos are huge — about five feet across — and accompanied only by a program in which the women wrote brief autobiographies.

“It’s almost as if you get a little personal tour by the women themselves,” Jay says, which gives allows the viewer to reflect on the images — and many other things.

“I realize it looks like it’s about breast cancer on the outside,” Jay says “but it’s about much more than that. It’s about compassion and love and fear and suffering and ultimately opening a dialog about death and suffering, just as a human being, which we all do.” In the western world we don’t want to talk about the fact that death will come for all of us, but “it doesn’t have to be scary. There are so many ways to live courageously, beautifully and without fear.”

David Jay

Showing this grace in its subjects is one of The Scar Project’s most potent elements, yet Jay worried that his instinct might have gotten in the way.

“I wanted The Scar Project to be very, very, very raw, just honest images of the subjects. I wanted any woman, any man, anyone, to look at the pictures and go ‘Yeah, that’s me. I’m suffering in the same way, maybe not from the same thing, but I’m scarred as well… but I see that you’re brave and somehow and beautiful in your honesty and I can be that too.’”

Yet, out of compassion and an understanding of what the women wanted — he is a fashion photographer, after all, capable of making people gorgeous — it was his impulse was to use all the tricks of his trade, like lighting and posing the subjects just so. Later he worried that other survivors would see these pictures and compare themselves to subjects he had expertly set up. They would not see that the hormone therapy had caused the subject to gain weight, that her skin wasn’t perfect, that those beautiful angles to her face might be the magic of millisecond of flash and perfect lighting.

“This isn’t about photography or fashion, this is about accepting ourselves as human beings and knowing and accepting our physicality. We are more than that. You must have more to offer than that. You must. If all you have to trade on is a nice set of tits and a $600 handbag you’re in trouble, because those could be gone in one doctor’s visit….We are so much more. That’s cliche, but it’s true.”

Having realized that he wants images to be more raw, he’s no longer going to shoot the women that come to him in his studio, because if he’s there “I can’t stop myself from taking a classically beautiful picture of you.” It’s a kind impulse (and any person who has ever been badly photographed — which is all of us — would be thankful for), but from now on, he says, he’ll shoot his subject where they are: in a hotel, at a friend’s house, in a stairwell.

“I know that even in their most raw state, if I was strong enough to take it, the beauty would come through, even with all the things we consider flaws, and everyone would find them just as beautiful. And that’s what happened, ultimately.”

David Jay

And yet his impulse did created a bridge for the viewers and for Jay himself to get to the reality of breast cancer. The Scar Project is, after all, meant to create awareness and people can’t be aware of something if they find it way too hard to look at. The Scar Project images are shocking at first, but their profundity and richness set in quickly and soon it’s hard to stop looking at them. Thus the message can sink in.

“The response to both (the photographs and the documentary) has been amazing, it appears to be 100 percent positive,” he says. “If I tell you I’ve gotten 5000 emails in five years, I’m not kidding.” They’ve been from survivors saying the same things: they were having a hard time accepting their bodies, were getting dressed in the dark, felt like no one would ever want to look at them again. The Scar Project changes their perceptions.

But all the stories don’t have happy endings. Some of these women will pass away. Jay is adding four pictures this year of women who are “kind of losing the battle,” and for the last couple of years has only been shooting pictures of women who are 30 and under who are in stage four cancer. Before his friend was diagnosed he didn’t even know you could get such a diagnoses in your 20s.

“I think everyone looks at it as their mother’s disease or their grandmother’s disease,” but that’s just not the case. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended in September that women get biennial mammograms beginning at age 50 (and that screenings should be determined case by case), though the American Cancer Society says mammograms should start at 40.

“Most of these women would have been dead if they had waited to be diagnosed,” Jay says.

And that’s the kind of thing Jay wants people to think about when they look at the Scar Project — not the artist, but the subjects, their grace, what they’re facing, and how other women can avoid it.

But for all its fearsomeness the photos are still breath-taking. “They’re so beautiful,” is an appraisal Jay hears frequently.

“Some people feel they have to say that for my benefit, or something,” he says. “I know they’re just talking about the soul of a woman.”

But David Jay isn’t a fashion industry caricature. Five years ago, when he was living in Australia a close friend of his was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 29 and had a mastectomy within two weeks of diagnosis. It was the genesis of a series of photographs that would literally change the way we see breast cancer: The Scar Project. Jay, a fashion photographer by trade, began taking pictures of breast cancer survivors, their nude or semi-nude bodies, their scars, their truth. The resulting photos are breath taking in their honesty, a reminder that we might be culturally more aware of breast cancer than ever but many of us have never really seen it.

The Scar Project had already been turned into a book and recently it became a documentary Baring it All, which premiered on the Style Network in July. The film follows four subjects through different stages of treatment and recovery. Director Patricia Zagarella, who Jay calls “an amazing filmmaker,” and the Style Network, “did it right,” he says. The doc “is a very, very accurate portrayal of The Scar Project,” though he agrees that the medium presents a different experience than the gallery setting. The photos are huge — about five feet across — and accompanied only by a program in which the women wrote brief autobiographies.

“It’s almost as if you get a little personal tour by the women themselves,” Jay says, which gives allows the viewer to reflect on the images — and many other things.

“I realize it looks like it’s about breast cancer on the outside,” Jay says “but it’s about much more than that. It’s about compassion and love and fear and suffering and ultimately opening a dialog about death and suffering, just as a human being, which we all do.” In the western world we don’t want to talk about the fact that death will come for all of us, but “it doesn’t have to be scary. There are so many ways to live courageously, beautifully and without fear.”

David Jay

Showing this grace in its subjects is one of The Scar Project’s most potent elements, yet Jay worried that his instinct might have gotten in the way.

“I wanted The Scar Project to be very, very, very raw, just honest images of the subjects. I wanted any woman, any man, anyone, to look at the pictures and go ‘Yeah, that’s me. I’m suffering in the same way, maybe not from the same thing, but I’m scarred as well… but I see that you’re brave and somehow and beautiful in your honesty and I can be that too.’”

Yet, out of compassion and an understanding of what the women wanted — he is a fashion photographer, after all, capable of making people gorgeous — it was his impulse was to use all the tricks of his trade, like lighting and posing the subjects just so. Later he worried that other survivors would see these pictures and compare themselves to subjects he had expertly set up. They would not see that the hormone therapy had caused the subject to gain weight, that her skin wasn’t perfect, that those beautiful angles to her face might be the magic of millisecond of flash and perfect lighting.

“This isn’t about photography or fashion, this is about accepting ourselves as human beings and knowing and accepting our physicality. We are more than that. You must have more to offer than that. You must. If all you have to trade on is a nice set of tits and a $600 handbag you’re in trouble, because those could be gone in one doctor’s visit….We are so much more. That’s cliche, but it’s true.”

Having realized that he wants images to be more raw, he’s no longer going to shoot the women that come to him in his studio, because if he’s there “I can’t stop myself from taking a classically beautiful picture of you.” It’s a kind impulse (and any person who has ever been badly photographed — which is all of us — would be thankful for), but from now on, he says, he’ll shoot his subject where they are: in a hotel, at a friend’s house, in a stairwell.

“I know that even in their most raw state, if I was strong enough to take it, the beauty would come through, even with all the things we consider flaws, and everyone would find them just as beautiful. And that’s what happened, ultimately.”

David Jay

And yet his impulse did created a bridge for the viewers and for Jay himself to get to the reality of breast cancer. The Scar Project is, after all, meant to create awareness and people can’t be aware of something if they find it way too hard to look at. The Scar Project images are shocking at first, but their profundity and richness set in quickly and soon it’s hard to stop looking at them. Thus the message can sink in.

“The response to both (the photographs and the documentary) has been amazing, it appears to be 100 percent positive,” he says. “If I tell you I’ve gotten 5000 emails in five years, I’m not kidding.” They’ve been from survivors saying the same things: they were having a hard time accepting their bodies, were getting dressed in the dark, felt like no one would ever want to look at them again. The Scar Project changes their perceptions.

But all the stories don’t have happy endings. Some of these women will pass away. Jay is adding four pictures this year of women who are “kind of losing the battle,” and for the last couple of years has only been shooting pictures of women who are 30 and under who are in stage four cancer. Before his friend was diagnosed he didn’t even know you could get such a diagnoses in your 20s.

“I think everyone looks at it as their mother’s disease or their grandmother’s disease,” but that’s just not the case. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended in September that women get biennial mammograms beginning at age 50 (and that screenings should be determined case by case), though the American Cancer Society says mammograms should start at 40.

“Most of these women would have been dead if they had waited to be diagnosed,” Jay says.

And that’s the kind of thing Jay wants people to think about when they look at the Scar Project — not the artist, but the subjects, their grace, what they’re facing, and how other women can avoid it.

But for all its fearsomeness the photos are still breath-taking. “They’re so beautiful,” is an appraisal Jay hears frequently.

“Some people feel they have to say that for my benefit, or something,” he says. “I know they’re just talking about the soul of a woman.”

Beautiful article. Thank you for sharing this.